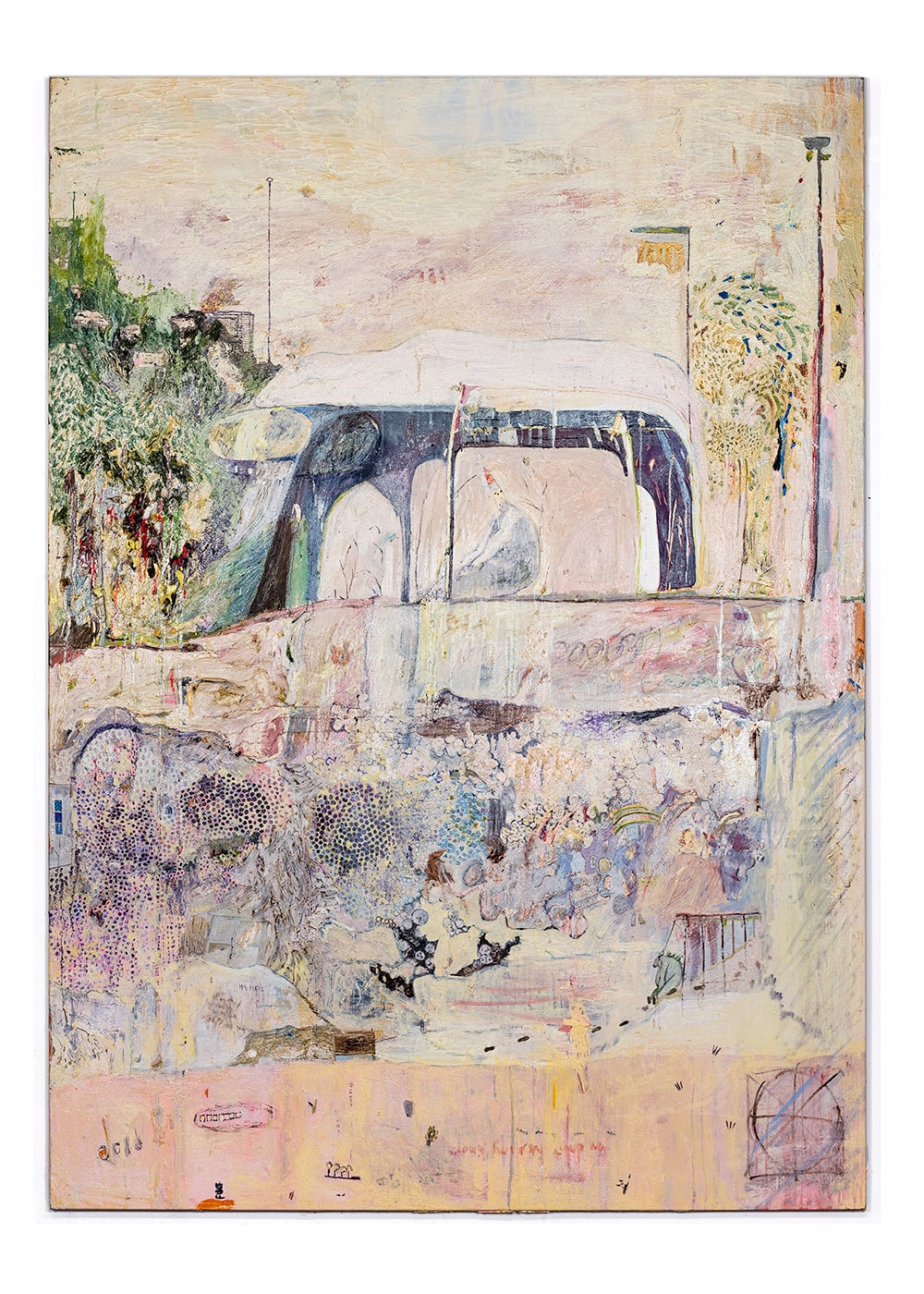

Un Cheng took up the artist-in-residence programme at Blindspot Gallery from late June to September 2020. Blindspot warmly welcomes Cheng back to the gallery, after her participation in our past group exhibitions Happily Ever After (2017) and Happily Ever After II (2018). Turning half of the gallery space into her studio, the artist was given carte blanche to experiment and create new works. In the name of the moon, I’ll punish you is the culmination of Cheng’s journey during the summer residency. In addition to paintings Cheng created in the past few months, Cheng’s solo exhibition will also display ephemera, drawings, sketches and tools that formed the ecosystem of her residency.

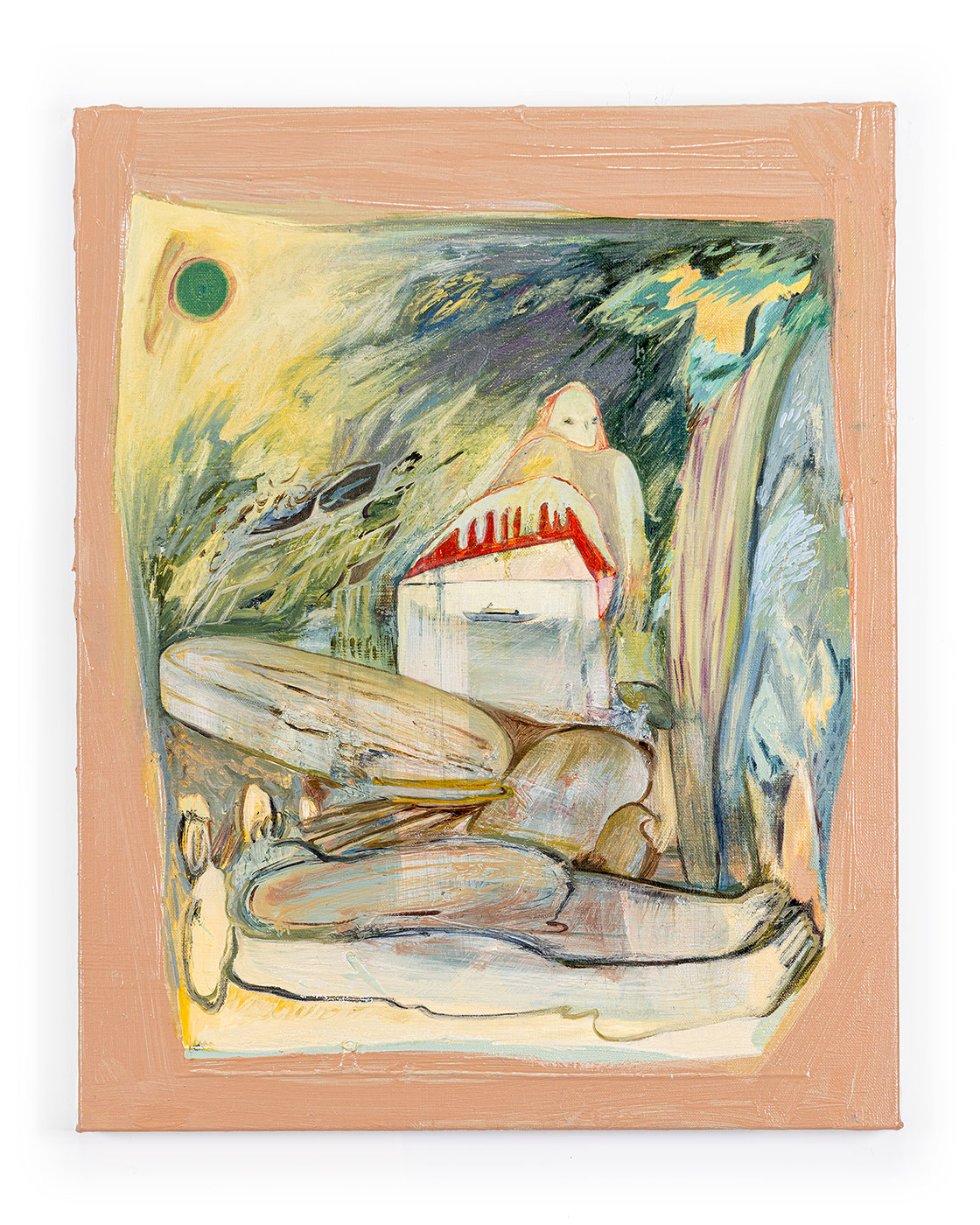

Cheng’s continuing practice centres on large-scale paintings, where the artist constructs grand vistas of the outside world filled with wondrous things like titanic ships and amphibious planes. Amidst this carefully choreographed chaos, the artist inserts sparse and often lonesome lilliputian human figures that represent herself. The vastness of space strikes an immensurable contrast with the smallness of self, the perceiver, the imaginer, the wonderer. This way of looking is manifested in Happy Birthday to Me (2019), a work Cheng conceived of after a month-long residency in Iceland. The artist experienced her birthday alone, in the near-perpetual darkness of a foreign winter. The soft glow of the moon softly illuminates layers of snow and the mosses underneath, and in her mind, they glitter like magical lunar crystals.

“In the name of the moon, I’ll punish you!” is the iconic provocation of Sailor Moon, the Japanese-anime beautiful schoolgirl moon soldier, before she strikes her enemy villains. Just punishment is the result of fair judgment, and vigilantism is the reaction when justice cannot be sought officially. Reflecting on the recent social movement in Hong Kong since June 2019, the painter evokes her disillusionment with heroism. Paradoxically, as the leaderless movement falters, Cheng finds herself yearning for a hero who can magically turn the tide and miraculously punish all evil doers. Against romanticism and naivete, heroism and justice are nowhere to be found.

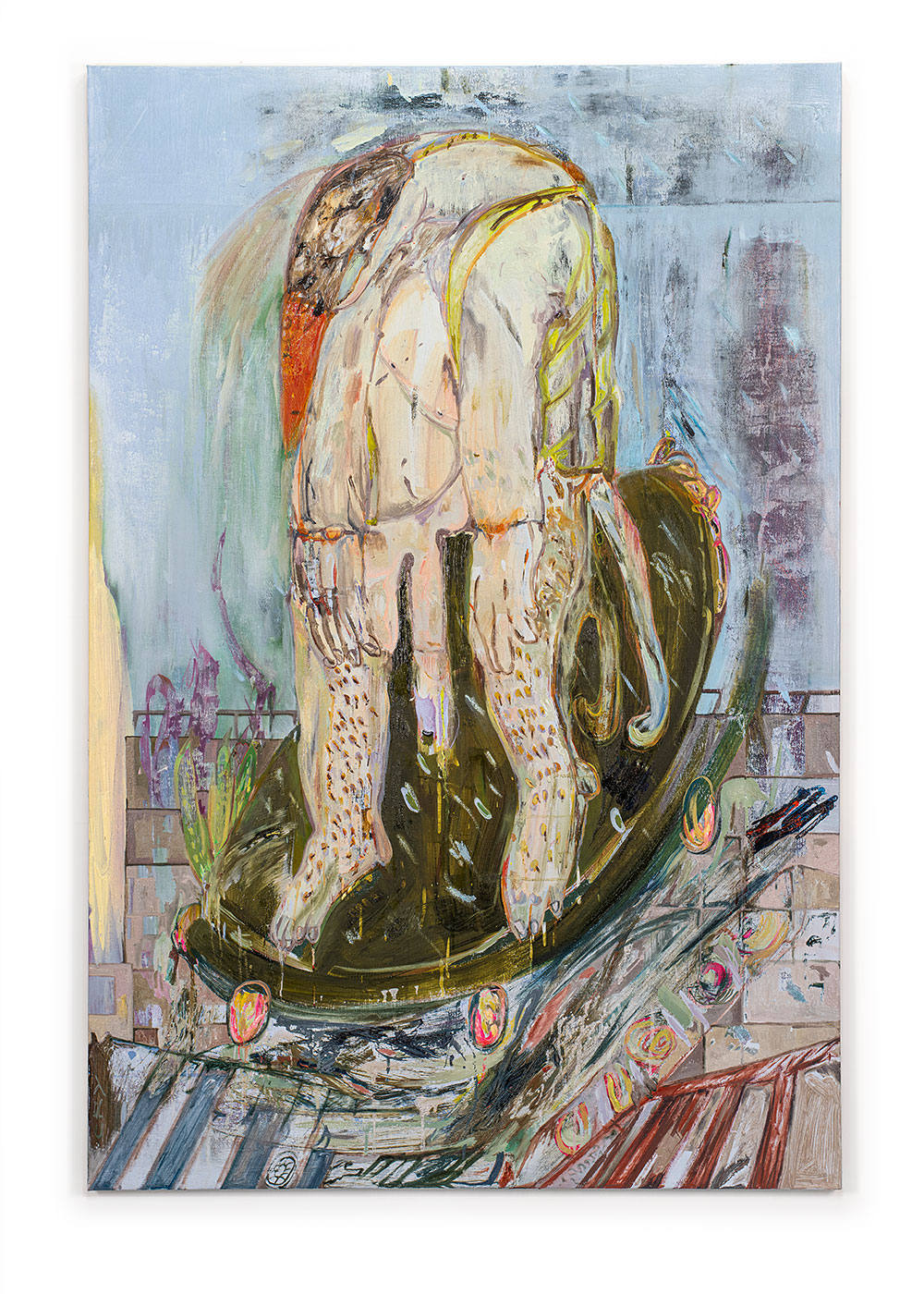

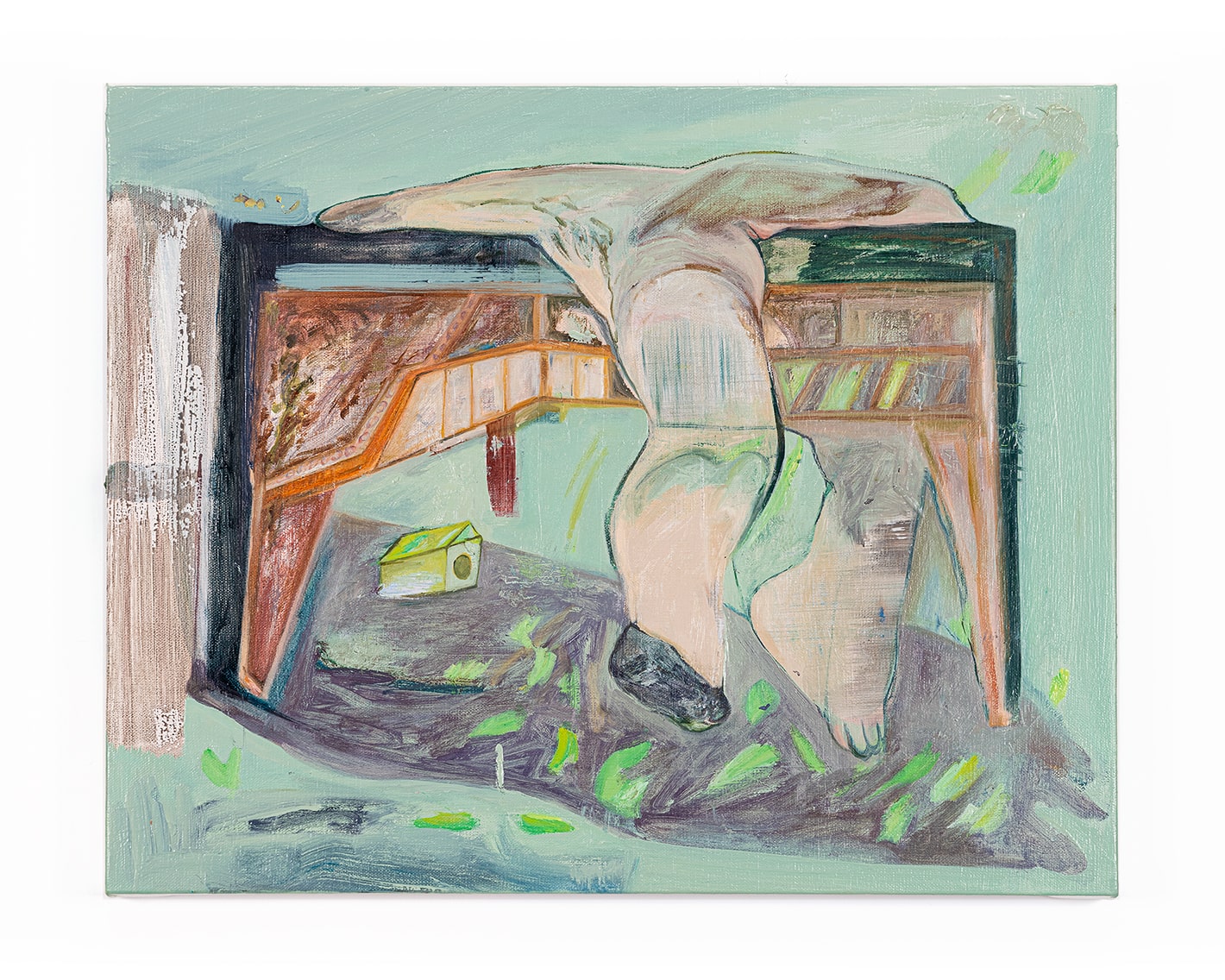

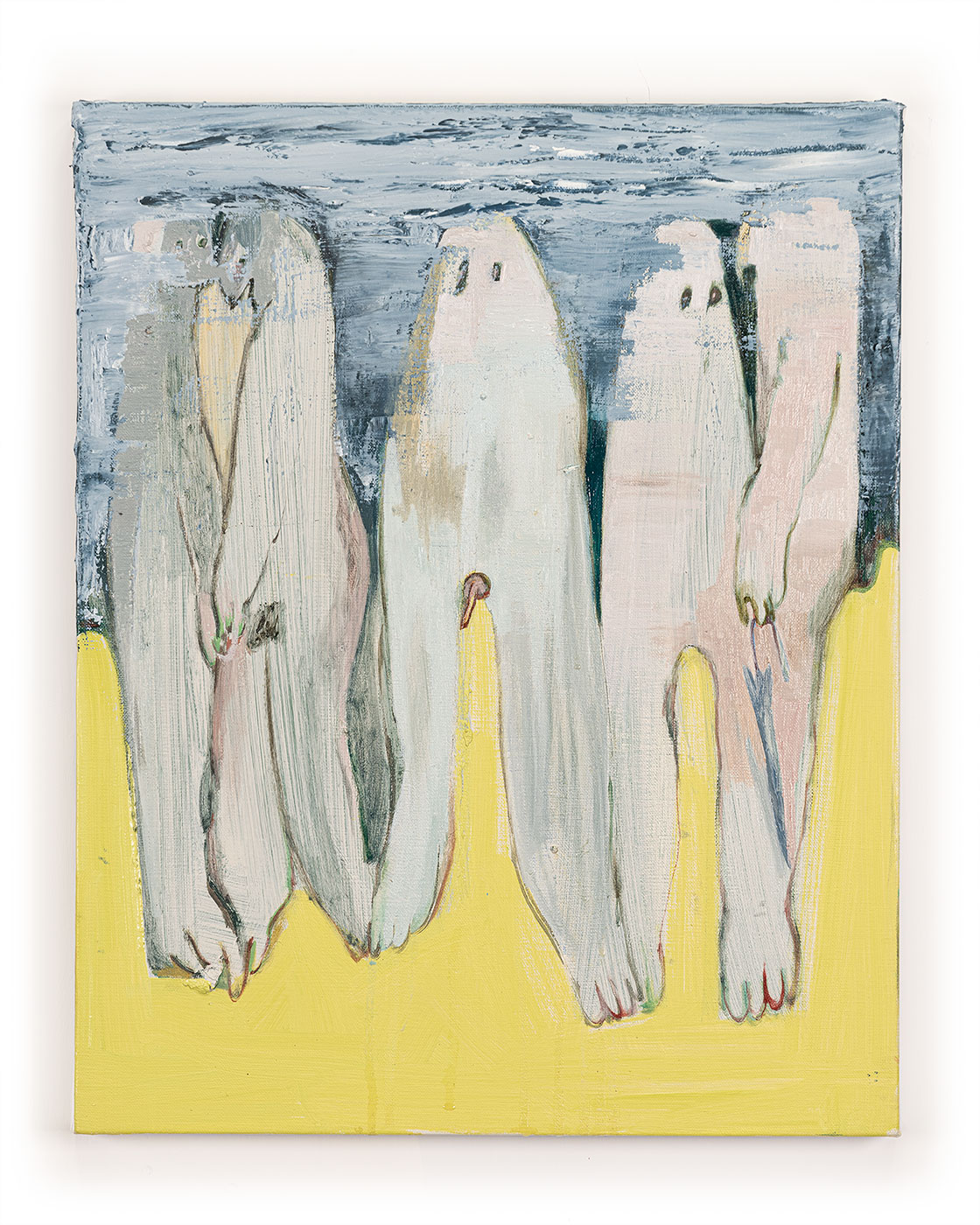

Cheng confronts how this world now occurs to her by pivoting from the expansive exteriority of landscapes to the intrusive interiority of gargantuan human figures. Teenage girls with bricks (2020) depicts a scene on the streets where gendered roles are clearly defined and women were discouraged from moving forward to the front. The huddling brick-digging girls stage a quiet protest against the testosterone-driven narrative of male heroism. The vulnerability of the female body becomes utterly visceral in Beer, Weed and Spinach (2020), when after a night of binging, the artist uncontrollably retches and purges everything from within. The complete collapse of bodily systems mirrors that of the society at large, except the purge never ends. Dysfunction pervades in Memory stretches as long as a rail (2020), where a man-beast on a skateboard slides defeatedly across sabotaged rails, its genitals and limbs flaccid despite stimulation. Wrecked, wretched and wrought, we all live in the rot, but some of us gaze at the moon.

)