Venue: Taipei Dangdai Edge Booth DG19, Taipei Nangang Exhibition Center (4/F Hall 1), Taipei City

Blindspot Gallery is pleased to participate in this year’s Taipei Dangdai, presenting a solo presentation of recent paintings by Un Cheng (b. 1995, Hong Kong) at the Edge sector. “Unbridled Wanders” traces the footsteps of the itinerant-wanderer artist traversing through the suburban corners of the city where nature and the man-made are closely intertwined. Based off photographs taken by the artist, Cheng paints a series of tableaus depicting the overlooked corners of quotidian life in Hong Kong. She accentuates the unappealing moments of the everyday that get omitted within the crevices, underlining their textures, material memories, humor, and awkwardness. The poetic visual journal lays bare the psychological landscape of an artist seeking solace and human connection amidst the ceaseless endeavors of a fast-paced metropolis.

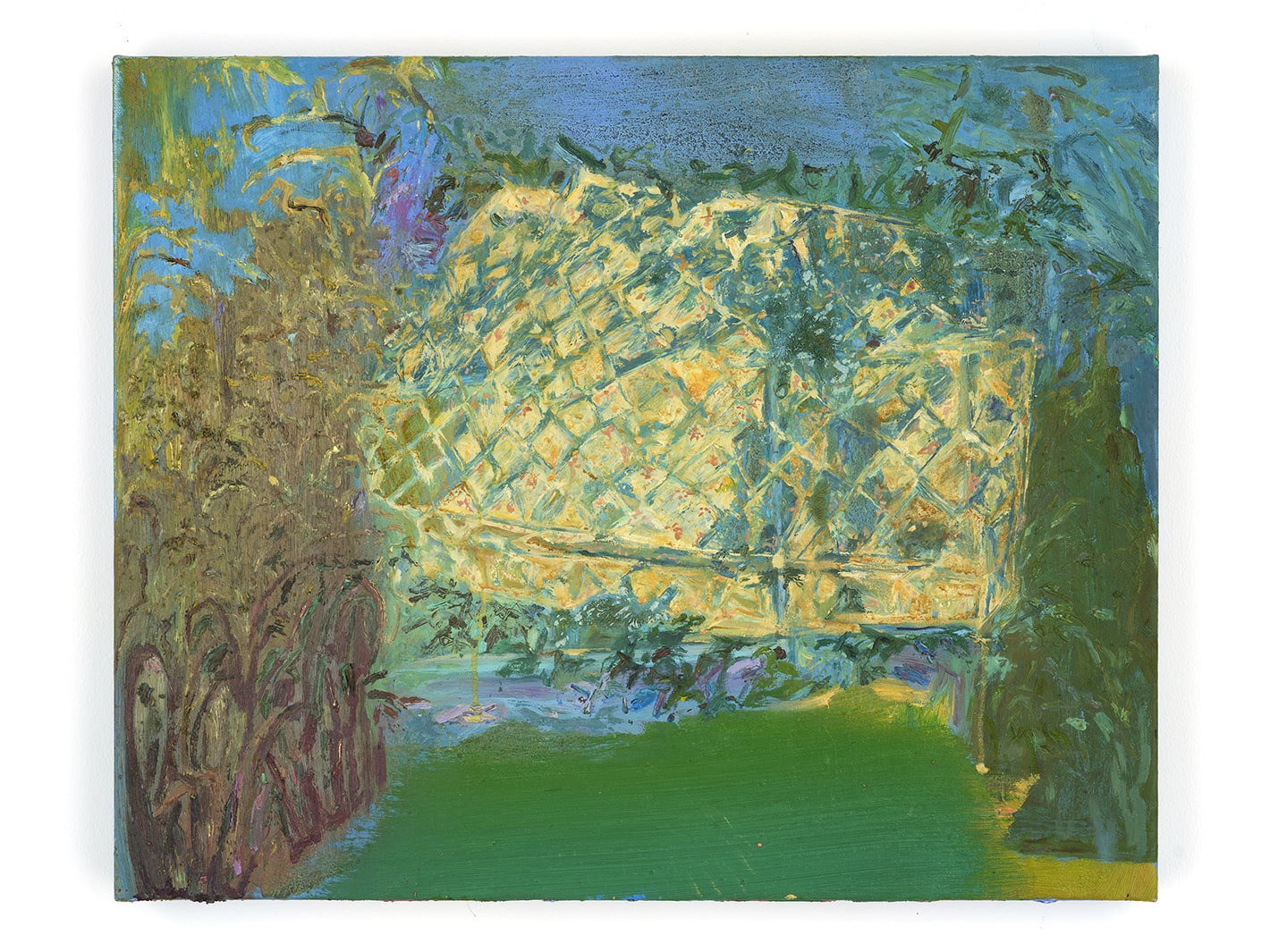

In The Flare Across West Kowloon, Cheng recalls a sweet moment of serendipity when she sat along the waterfront with a close acquaintance in the late nocturnal hours, only to be enraptured by sudden bursts of blue and yellow sparks emerging from the far side of the sea. They discovered them to be fireworks being set off from Disneyland just over the horizon. In The Mattress Things, Cheng stumbles upon a bed peculiarly parked between trees and shrubs in the middle of the mountains. The mattress lies atop luscious green grass, transforming into a secret haven for the restless nomad. Cheng finds consolation in this deserted mattress misplaced within the wilderness.

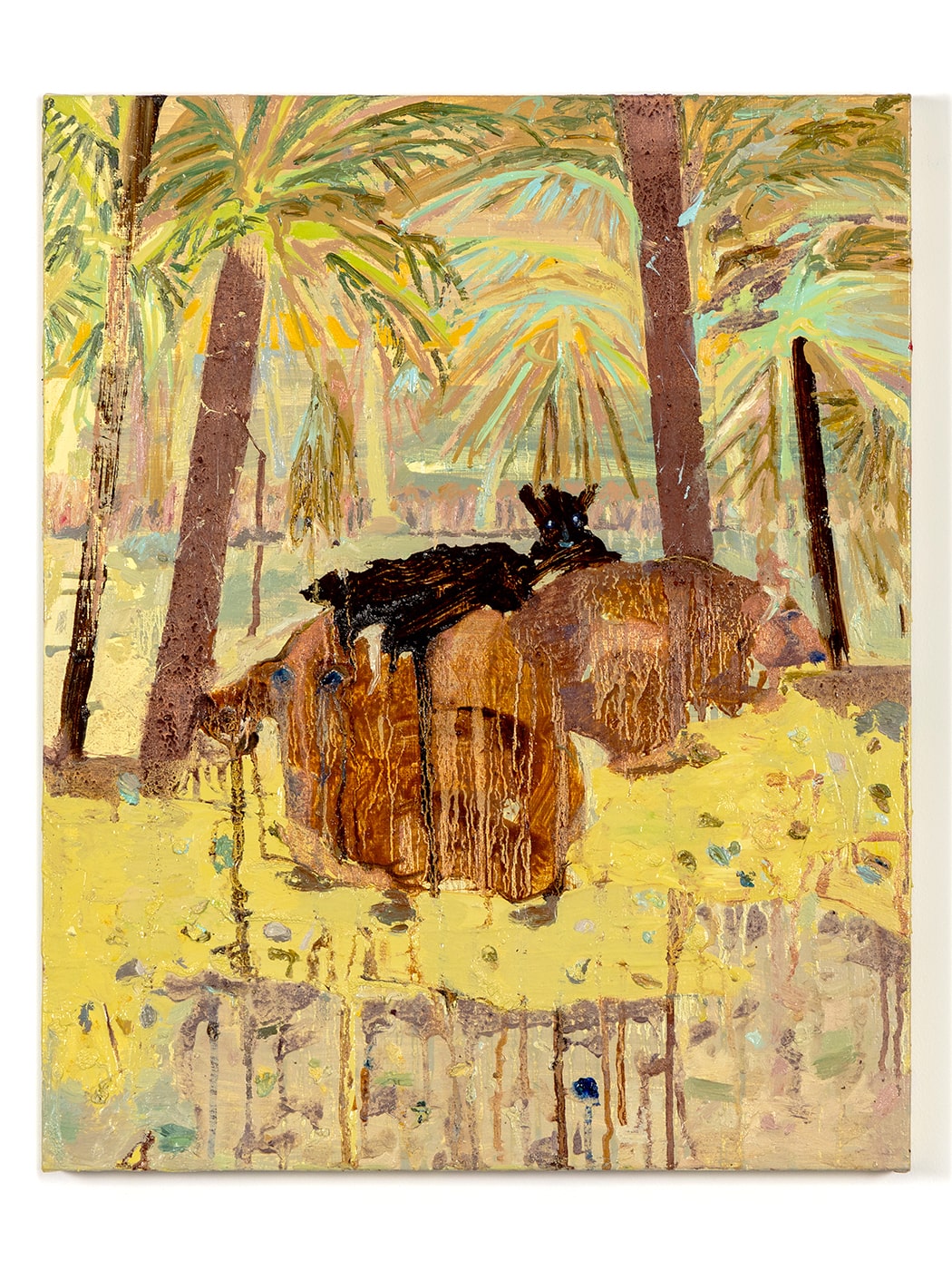

The artwork Ramen in My Heart depicts a rural landscape in warm orange and yellow tones. This color selection is a departure from the artist’s usual portrayal of landscapes in blue-green shades. Cheng believes that the finished painting resembles instant noodles, particularly her favorite Korean spicy noodles hence the name “Ramen in My Heart” which is a pun on the Cantonese phrase “There is you in my heart” ( 心裏面有你 ).

Is there “you” first? Or is there “noodle” first? Everything is but a reflection of one’s inner self. The interplay between image and text often appears in Cheng’s creations wherein visual experiences instantly evoke memories or emotions which are then transformed into an imagery. The resulting image may also produce associations or meanings in words, this is an interconnected creative process by the artist. Naming her artworks is also an essential aspect of Cheng’s creative process. She often uses Cantonese slangs and puns, reflecting both her rootedness in Cantonese culture and her humorous playful personality.

Cake which is emblematic of naivety and wonder is a motif that recurs in Cheng’s pastel-colored canvases. In The Christmas Dump, a wholly uneaten cake is thrown into the dumpster. Decorated with Christmas ornaments and a turquoise dinosaur, the golden embellished cake sleeps comfortably on a pile of pink trash. The festive cake, appearing creamy and scrumptious, melds into the swirly chaos, giving the ugly garbage a sudden merry appeal.

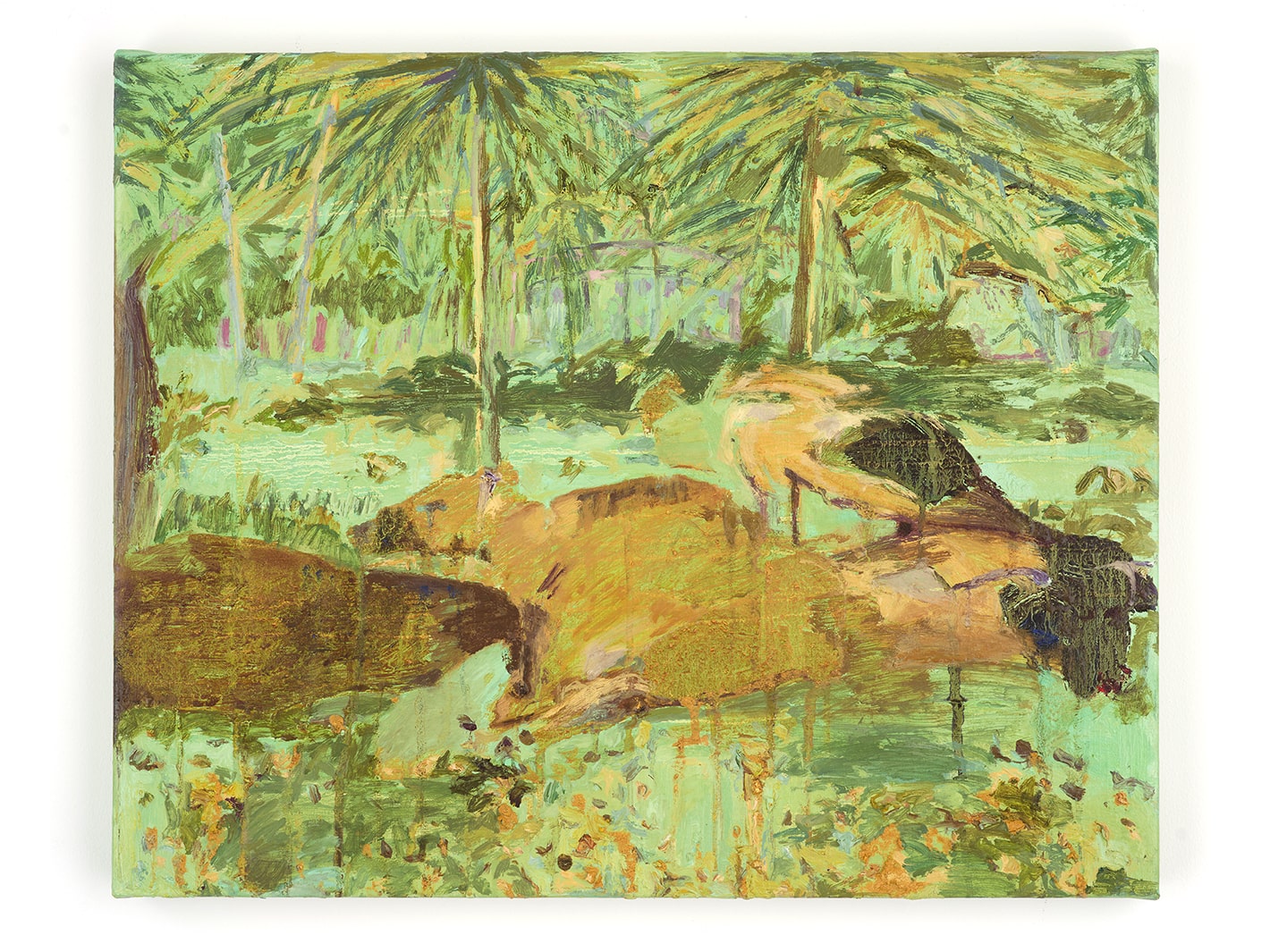

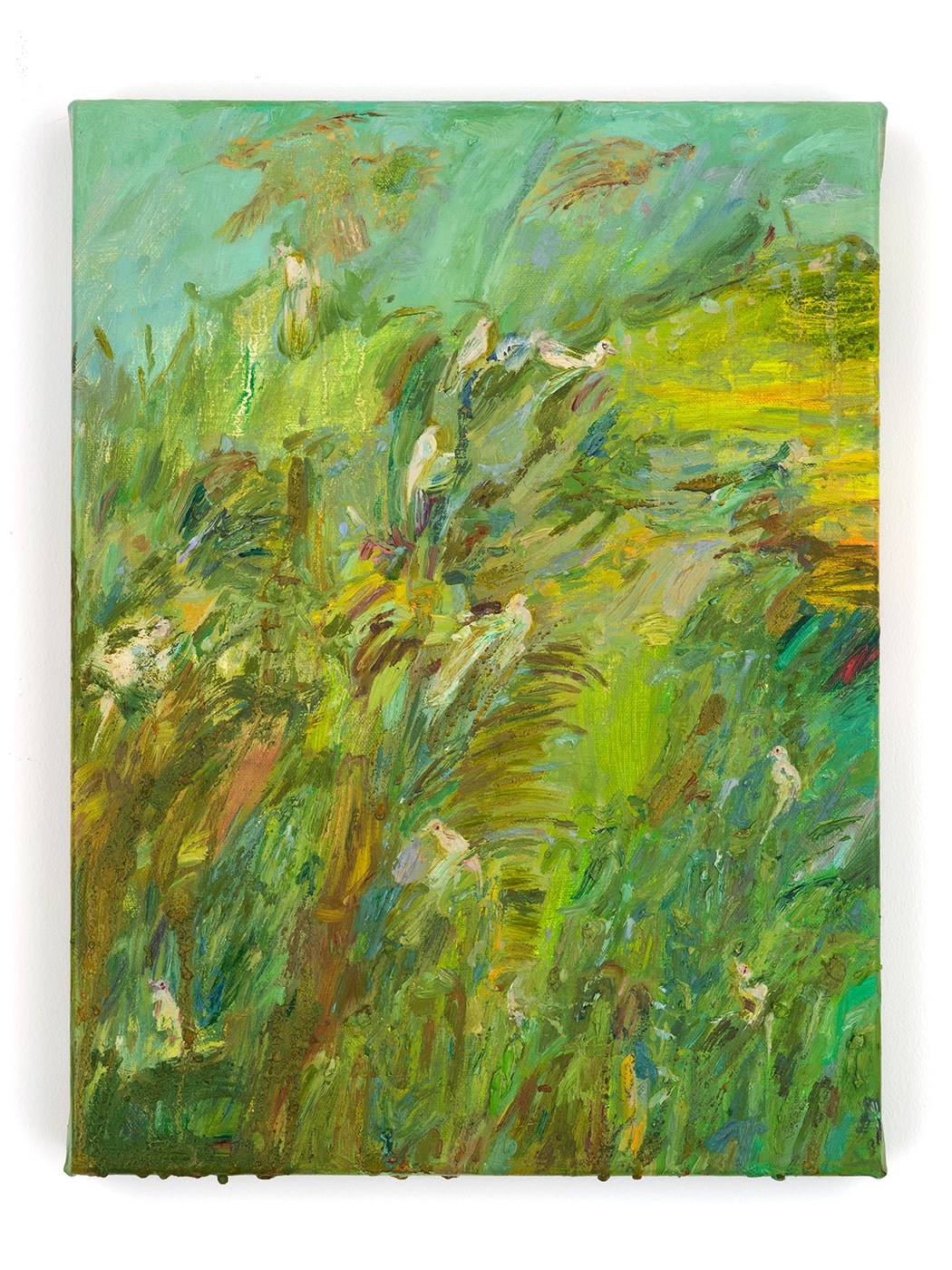

Cheng observes the zany mismatch between nature and human civilization in the suburban neighborhoods of Hong Kong. In Ox Tears I and II, Cheng portrays the oxen that recline leisurely by the promenade in downtown Sai Kung district, unfazed by the bustling crowds swarming in for weekend seafood shopping and junk boat parties. The artist is amazed by the animal’s utter indifference towards human activities, going about their daily routine as per normal. Similarly, in The birds don’t sing, the egrets nestle snugly in a tall tree by a bustling road in Tai Po, undaunted by the beeping traffic and human activities that surround them.

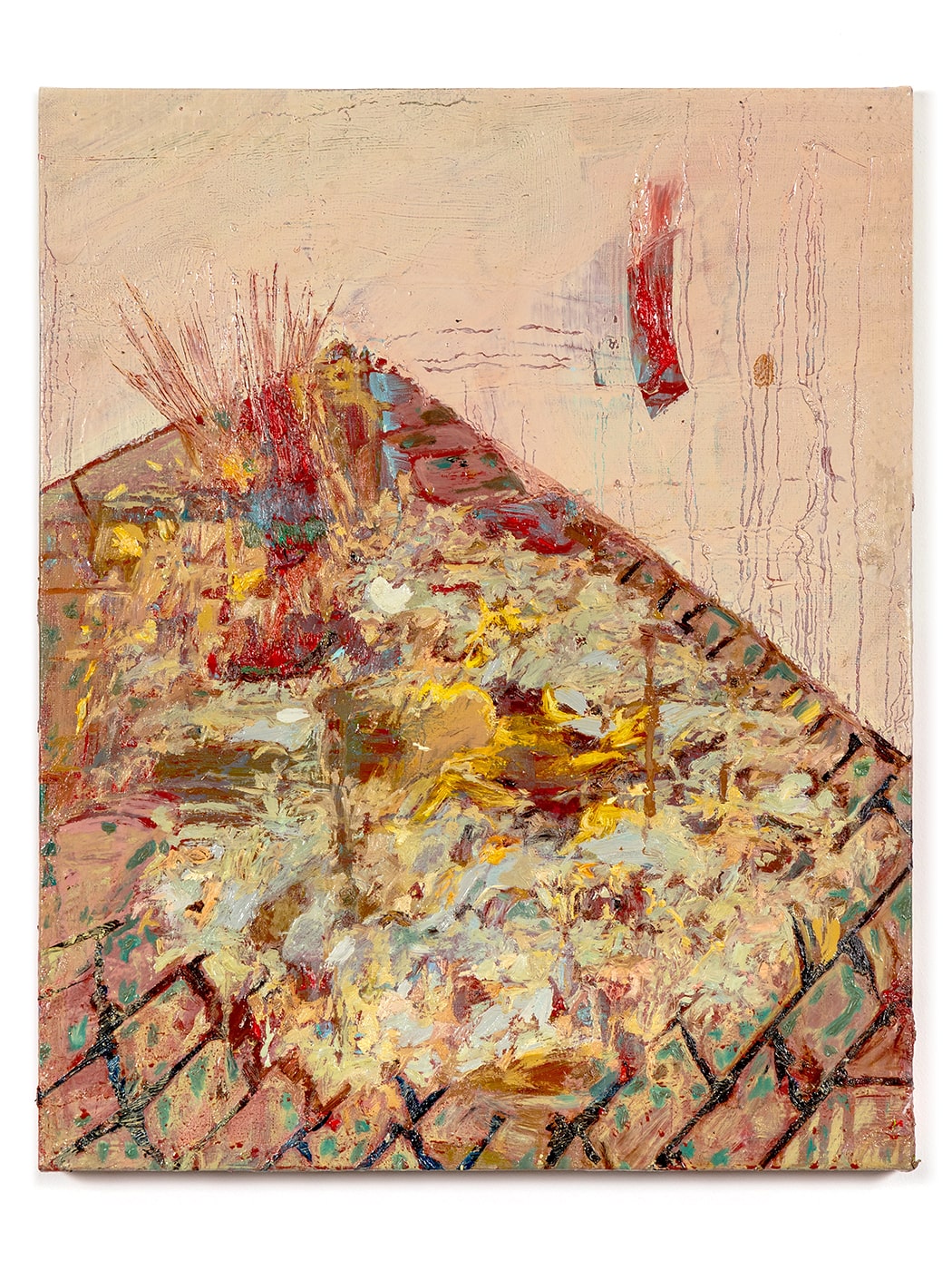

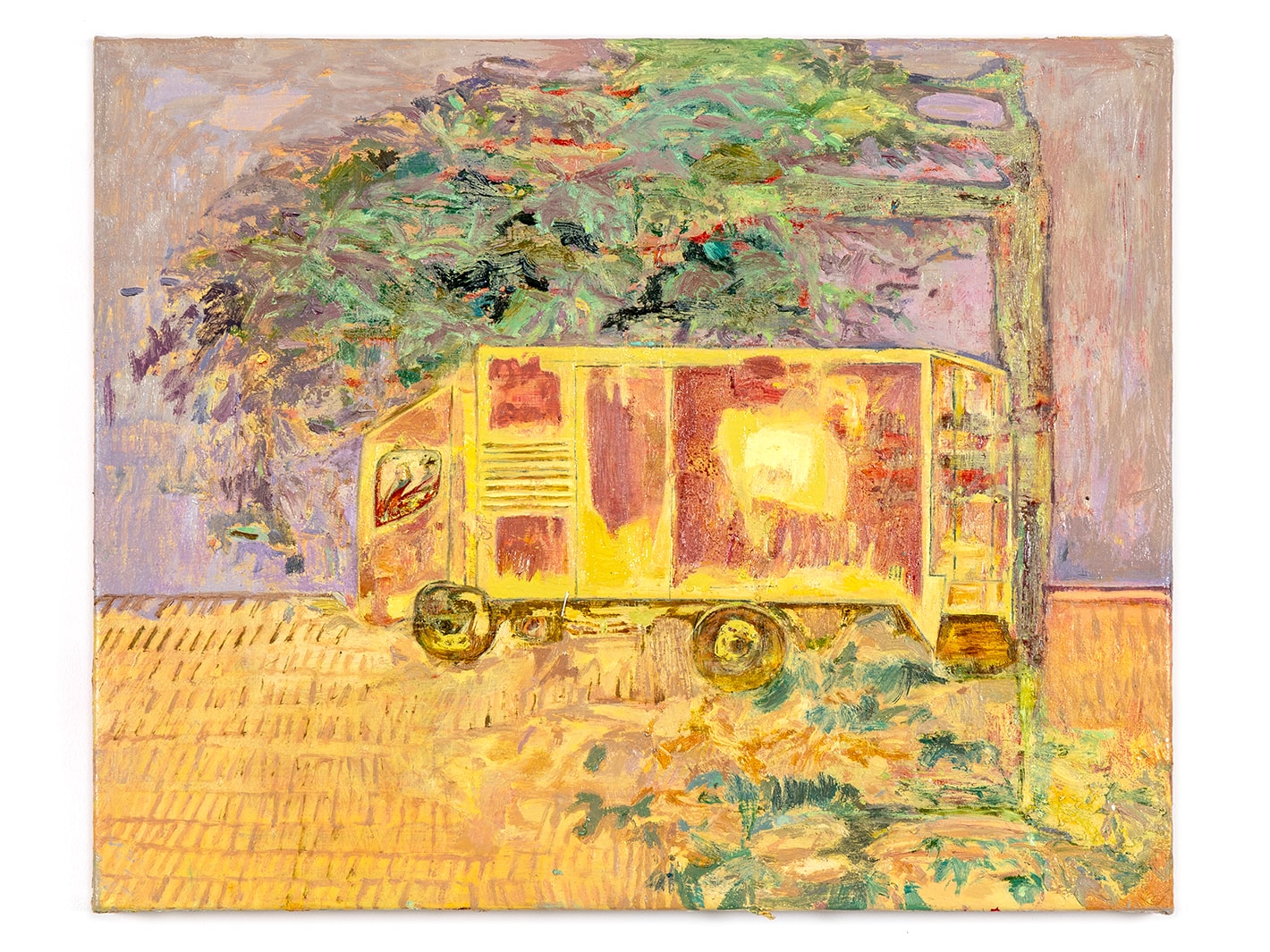

Cars are centered as a subject in Cheng’s painted scenes, personifying human sentiments in a barren landscape. In Kirin’s Frenzy, a desolate car is precariously parked up against a steeping slope. The automobile is in an uncomfortable state of limbo, metaphoric of one’s disconcerting emotions. In biu biu biu, Cheng recreates a vivid impression of a yellow truck shimmering in the evening, parked clumsily in the middle of the road where all can see. In Friend Ship to Universe, Cheng portrays a silver covered car melding into the amorphous trees and shrubs, losing its form as it dissolves into abstraction. The image is emblematic of a friendship that slowly dissipates into thin air.

A few works capture Cheng’s fleeting dialogues with strangers that are at times wondrous and hilarious; at other times poignant and captivating. In NO BARGAIN $10!, a street vendor bends down to reach for the vegetables, unveiling the rich floral pattern on her shirt which mirrors the vegetables she sells. Offended by Cheng taking her photograph, the lady persuaded her to buy from her store as a “fair trade-off”. When asked for a bargain, however, the vendor was swift to refuse. In another scene, Foo Fighters, Cheng depicts an uncanny interaction with an elderly man who swims ceaselessly in the canal to reach for a ball before locking eyes with her when she takes his picture. They exchange looks awkwardly before the man unfreezes to resume his swim, their brief interaction leaving an indelible impression on the artist.

The narrative behind Incapable Cable stems from the artist’s encounter with a worker while passing through a street in Tai Po District. The worker was seen chopping a tree, his body drenched in sweat, his appearance reminiscent of Master Li Mu Bai. Master Li was the character played by Chow Yun-fat in Ang Lee’s acclaimed film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. The artist instantly gave this man the nickname “Master Li Mu Bai of Tai Po”, befitting of his masculinity and heavy labor.

These serendipitous, erratic, and whimsical associations often derive from Cheng’s life experiences and memories, a means through which she acquires inspiration for her paintings. This approach often reflects how Cheng is moved by interpersonal relationships in her daily lives. Not merely do her works encapsulate her observations of human connections but they also exhibit intimacy and humor.

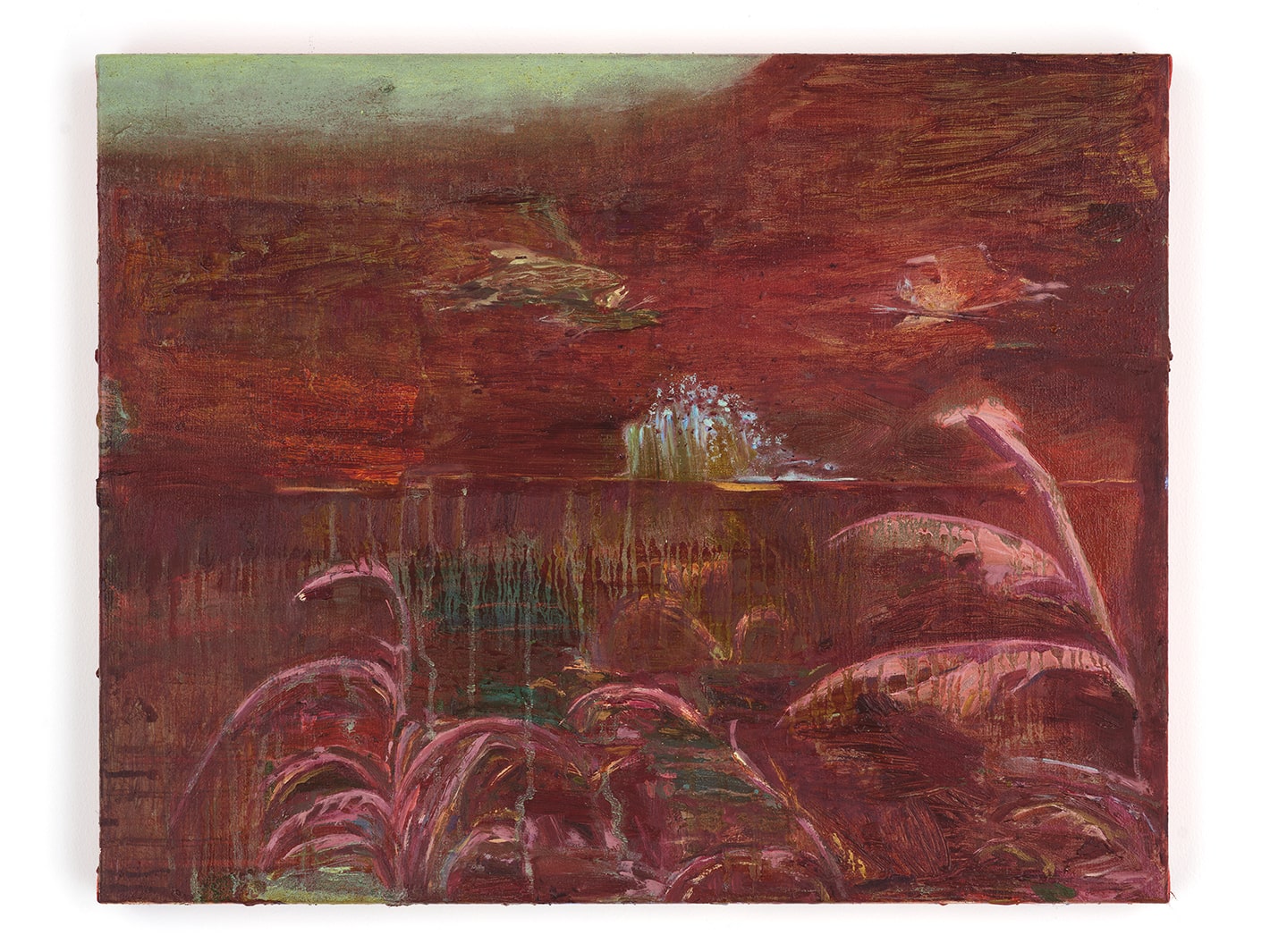

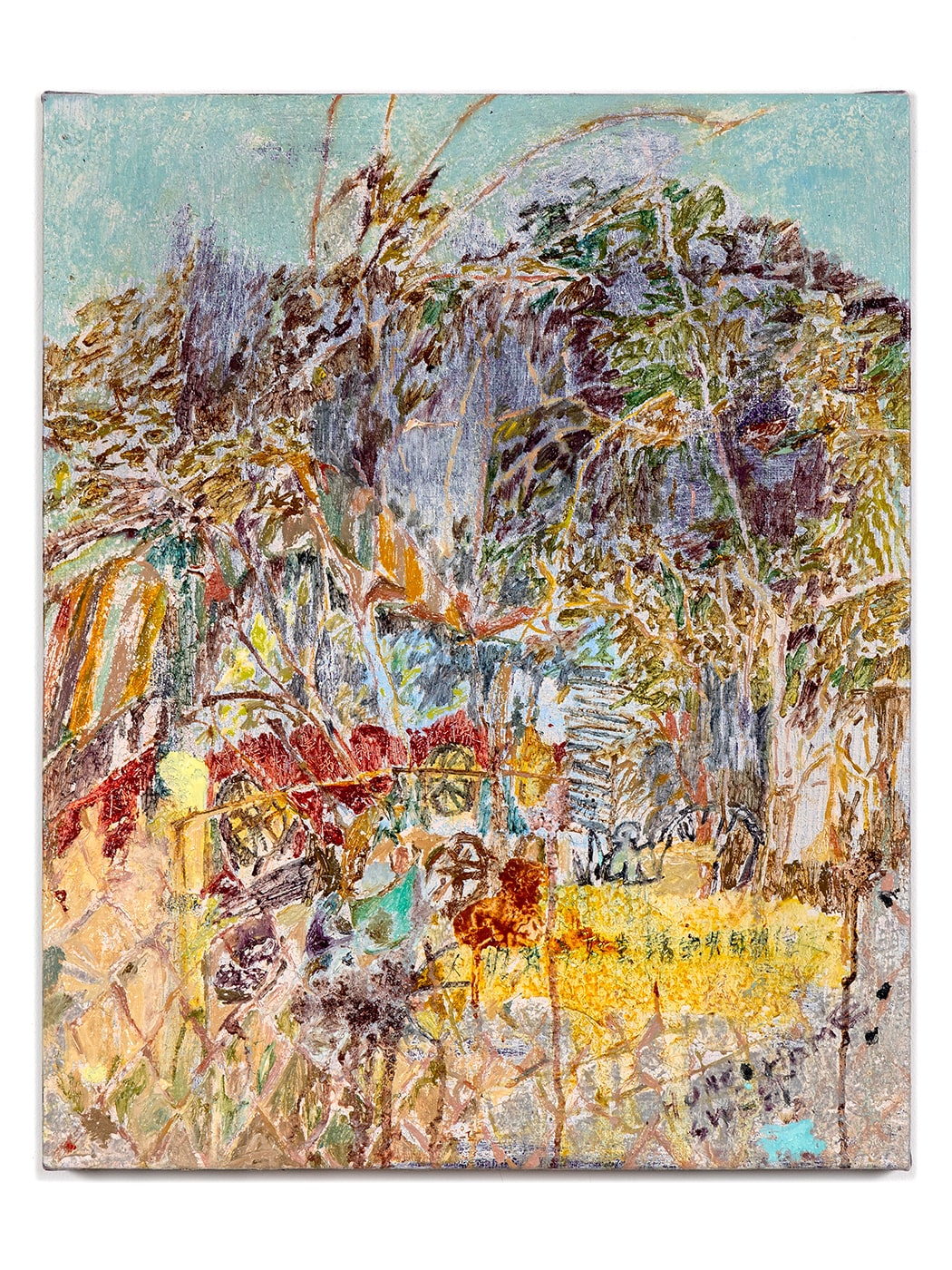

In Cinder, Cheng delineates a somber encounter with a woman burning joss papers for her deceased daughter in the late hours of the evening. The ashes and flames scatter across the tiled floor, lighting the street aglow in a calming yet melancholic manner. Devoid of human figures, the painting bears palpable traces of the mourning mother. Cheng ends her series with People’s common imagination for a better life. In a sketchy tableau, Cheng encapsulates the idiosyncratic textures of the city’s gritty suburb, dispersed with trees, houses, tires, broken wire fences, and the occasional playful dog. It captures Tai Po neighborhood where since 2022 Cheng has had her artist studio that doubles as her living space. Cheng’s patchy brushstrokes evoke the disarray of the scene which lies as an ironic contrast to the sign that reads “people’s common imagination for a better life”. Despite the clutter and chaos, Cheng signs off with a touching remark of “home sweet home”.

)

)

)

)