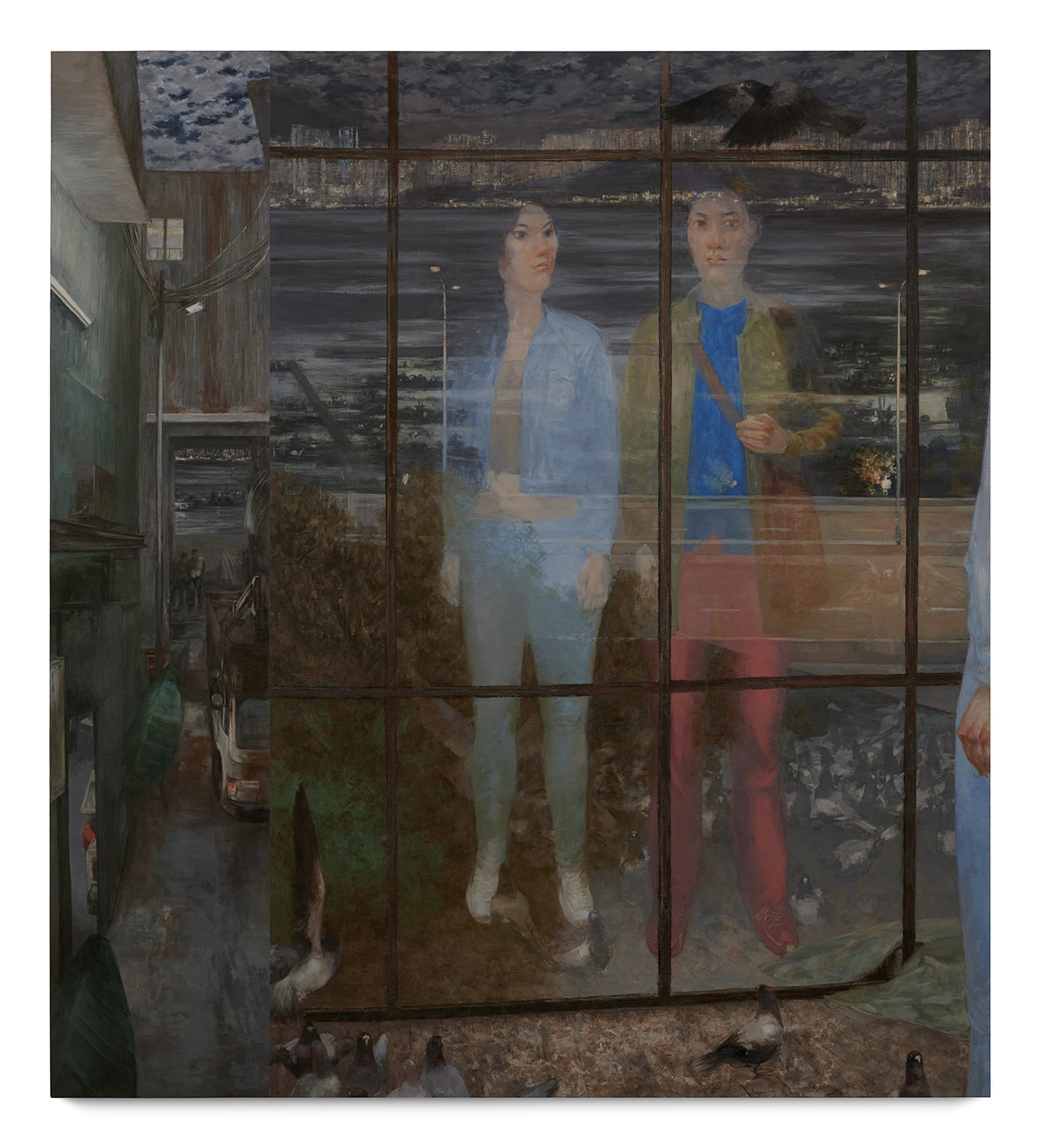

Blindspot Gallery is pleased to present Daily Practice, a solo exhibition by Yeung Tong Lung, in collaboration with Art & Culture Outreach. This major solo exhibition features the artist’s most recent works executed in 2019-2020, in addition to selected works from 2015 to 2018. Daily Practice proposes an expansive reading of Yeung’s paintings, a practice that spans four decades and myriad styles, but consistently based on an intimate observation of people, nature and things with whom the artist shares his existence. Painting for Yeung is a daily practice — a patient practice for internal and external growth, and an imaginative practice for representing the richness of interior worlds beyond surfaces and despite circumstances.

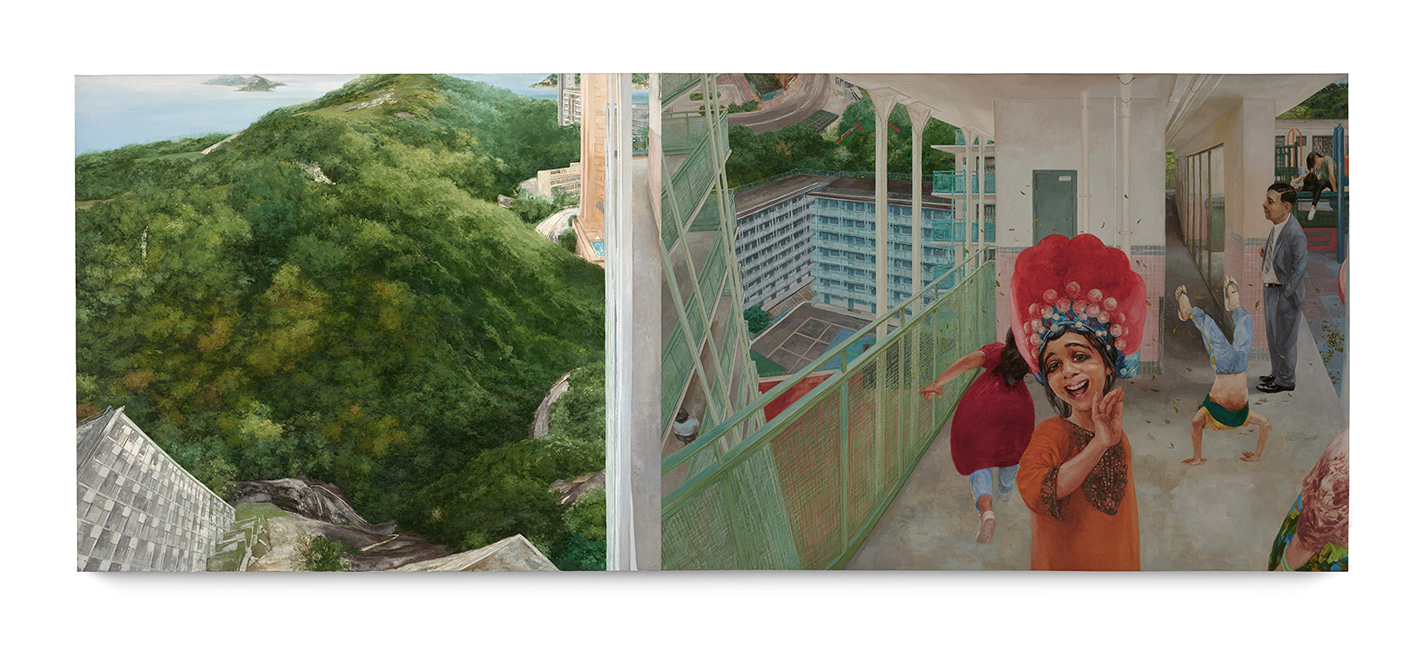

The pièce de résistance of the exhibition is Mount Davis (2020), a 4.5-meter-wide tripartite history painting that meanders through a number of disparate scenes, striking an uncanny connection between different historical moments. In 1950, Mount Davis was the site of refugee camps for Kuomintang (KMT) soldiers and families. The colonial government relocated the soldier village after the Yangge Dance Incident in June 1950, when a leftist group descended upon the village waving the PRC flag, performing the then popular-with-communist Yangge dance and provoking the KMT villagers, resulting in tens of people injured.

Hints of displacement, violence and unease pervade the triptych painting. Yeung stages and choreographs a careful cinematic pan shot that transitions through different mise-en-scène, from night to day, from exterior to interior. The left panel of Mount Davis shows an elevated view of the squatter village that stretches all the way downslope to the sea, while a cautious line of people snakes along the dark ridges of the mountain, uncertain if on mission or to flee. The middle panel shows the inside and street view of a Chinese bone-setting clinic in the village, where an elderly treats a young man with an ankle injury, while a man in dark overcoats linger in the background, his repeated presence ominous and motivation unknown. The right panel is unveiled by an African woman in a safety vest, who is hosing down the site behind, but the reason for the cleanse is untraceable. To the further right is a police cage car with two youths arrested, and from the winter uniform of the policeman and the fashion of the detained, one can deduce that this is a scene from the 1966 riots against the colonial government’s decision to raise the Star Ferry fare. The artist relinquishes linear narrative and unified temporality, in favour of a fragmented picture plane loaded with an expansive range of details and stories, figures from his own life and figments of imagination. It is a painting that raises more questions than it answers – a twist to the practice of history painting that befits our contemporary moment, when truth evades and information overloads our existence.

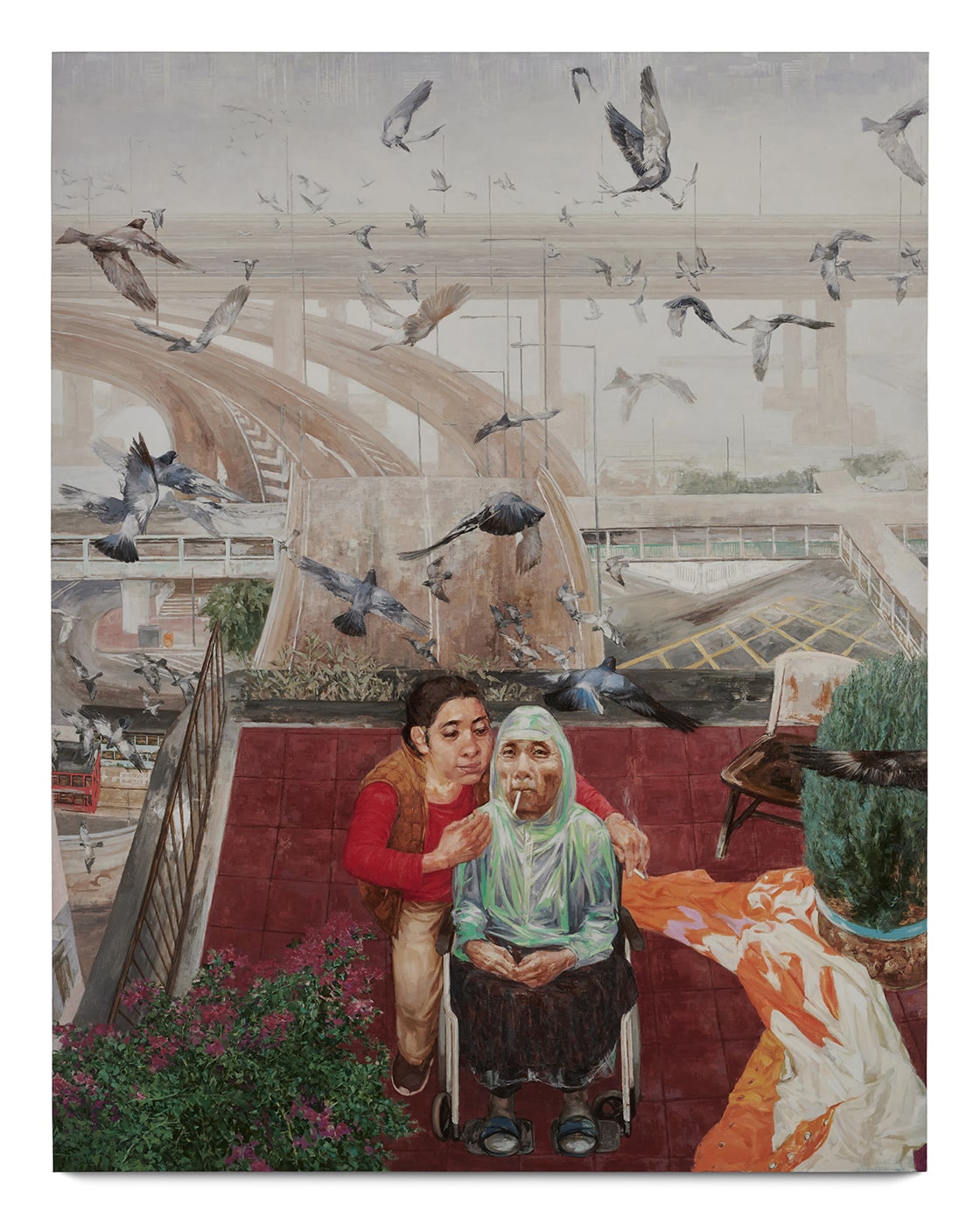

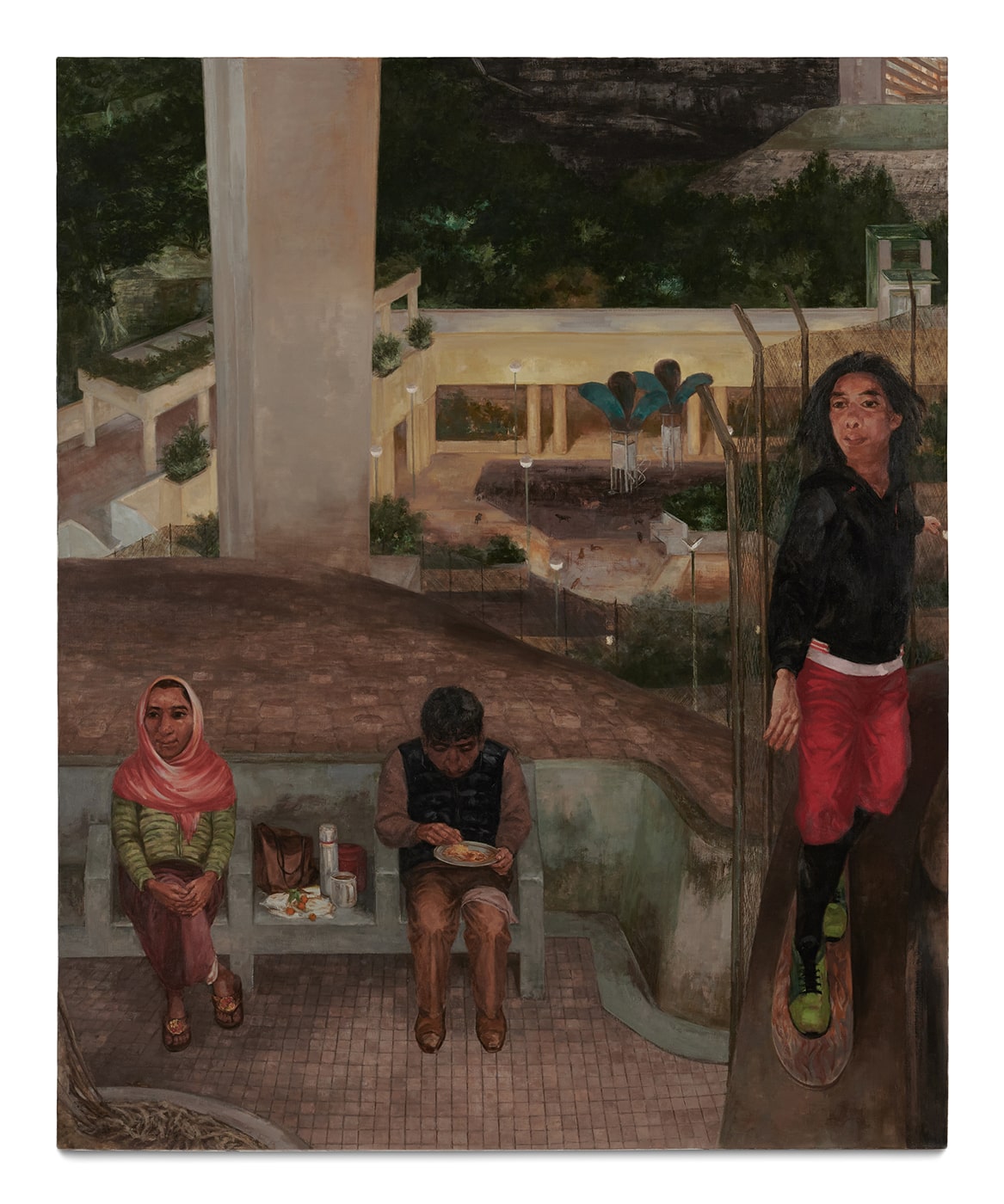

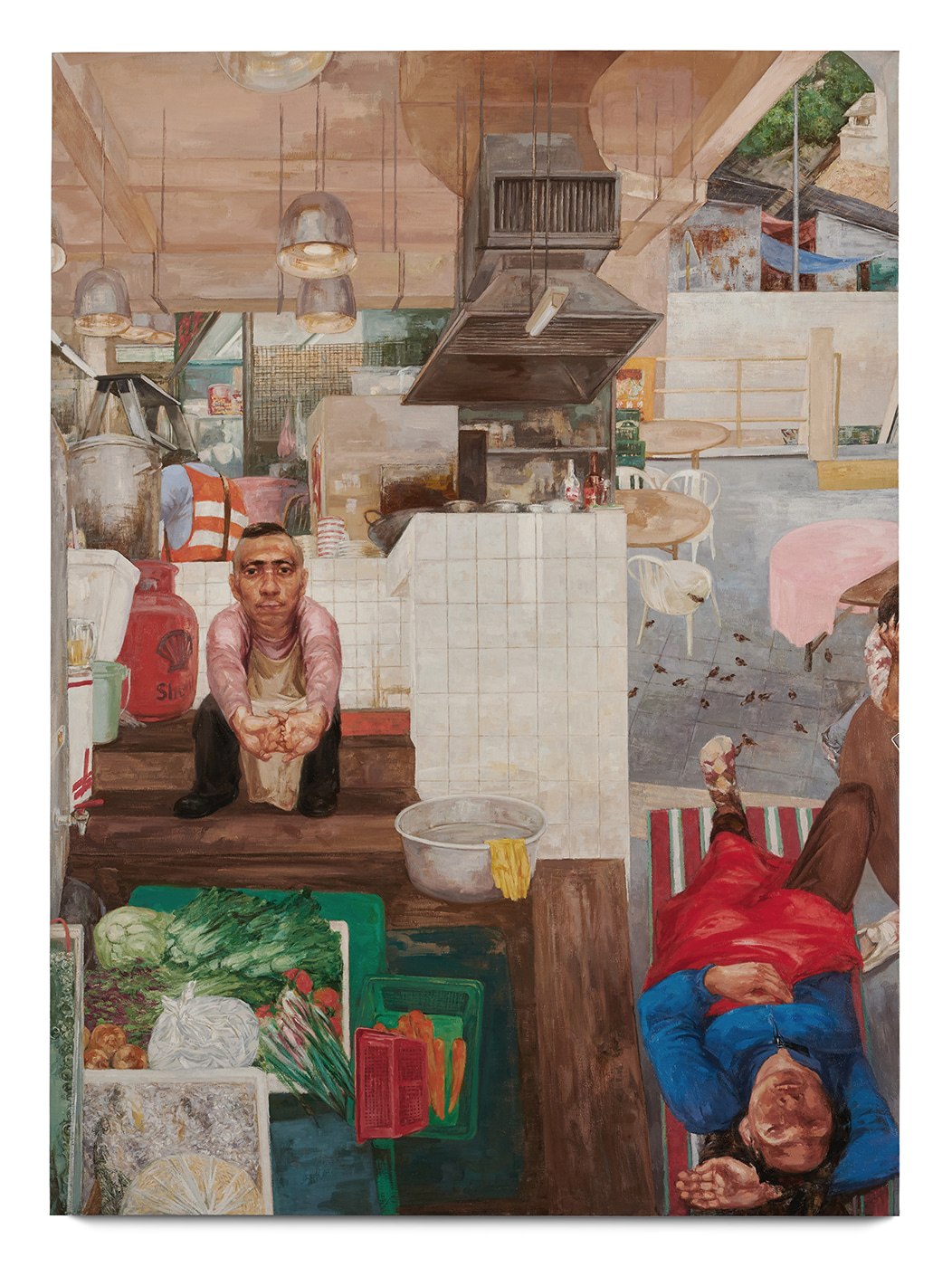

Away from big history, other works return our gaze to the small quotidian life, and capture the wide spectrum of existence in the city, which is expressed in moments of intimacy, buoyancy, idleness, withdrawal, and dejection. Have a Smoke (2020) captures a moment of tenderness and care, as an elderly sits hunched over in a wheel chair with an unlit cigarette, while the caretaker lights a cigarette for herself, sharing a little moment of respite and a breath of fresh air. The rooftop boasts a spectacular view of the city, while a school of wild pigeons ascend in a frenzied flight. The pigeons’ freedom contrast sharply with the immobility of the wheel-chair-bound and care-ridden humans. King of Siu Chao (2020) shows a stir-fry eatery where employees are taking a break while a repairer rummages through the kitchen. The chef is stretching his joints and his back, assuredly gazing at the viewer, while another worker on the right rests horizontally on a bench. The break is brief, for the night time dining crowd shall come soon and the raw food in the foreground lies ready to be cooked. In a gesture of grace and care, Yeung imagines his subjects in moments of respite, reverie, and escape. These redundant moments, though brief and fleeting, create a fissure from the immutable continuity of existence, a reprieve from the monotony and necessity of work, and most importantly, a promise of future happiness.

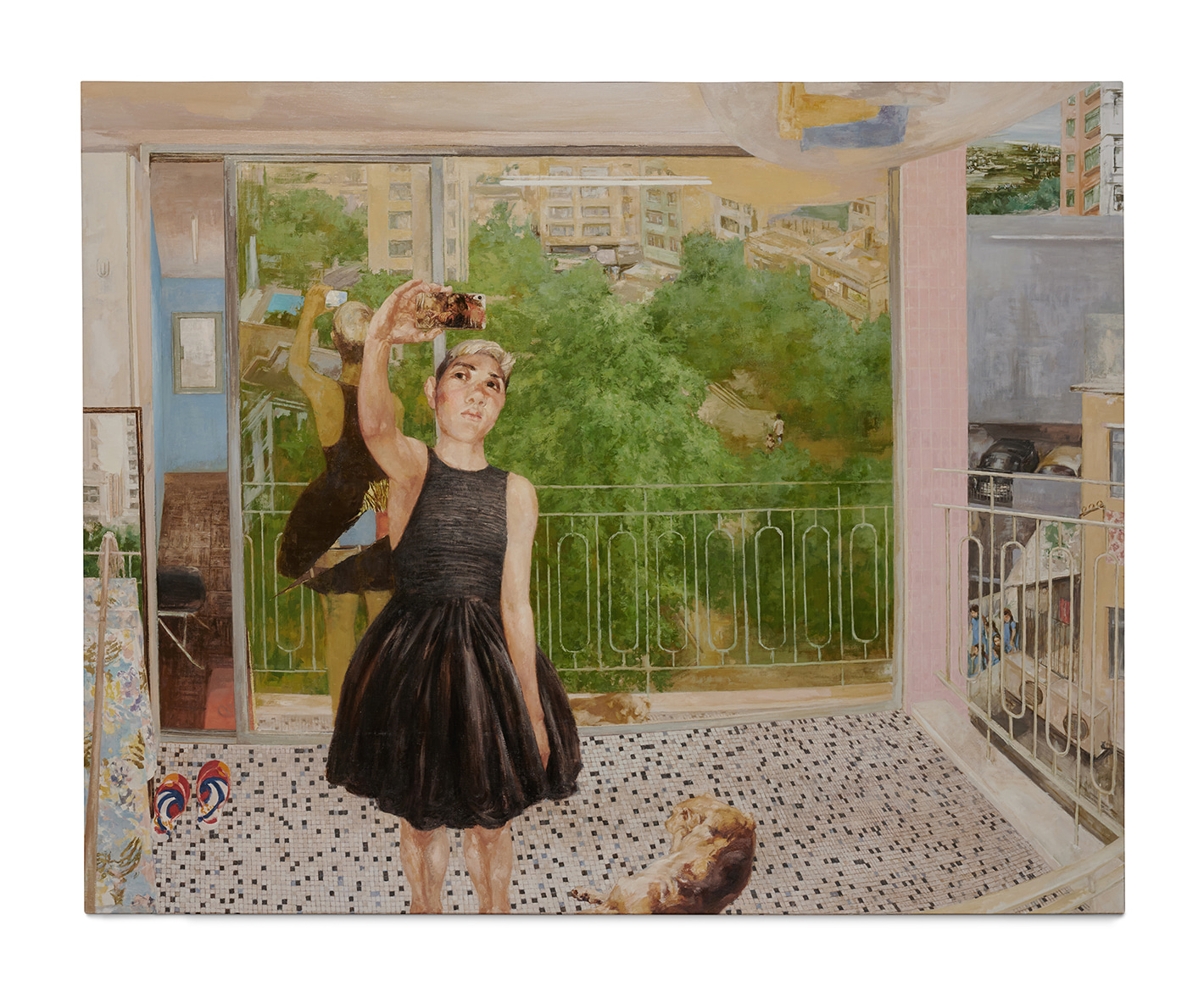

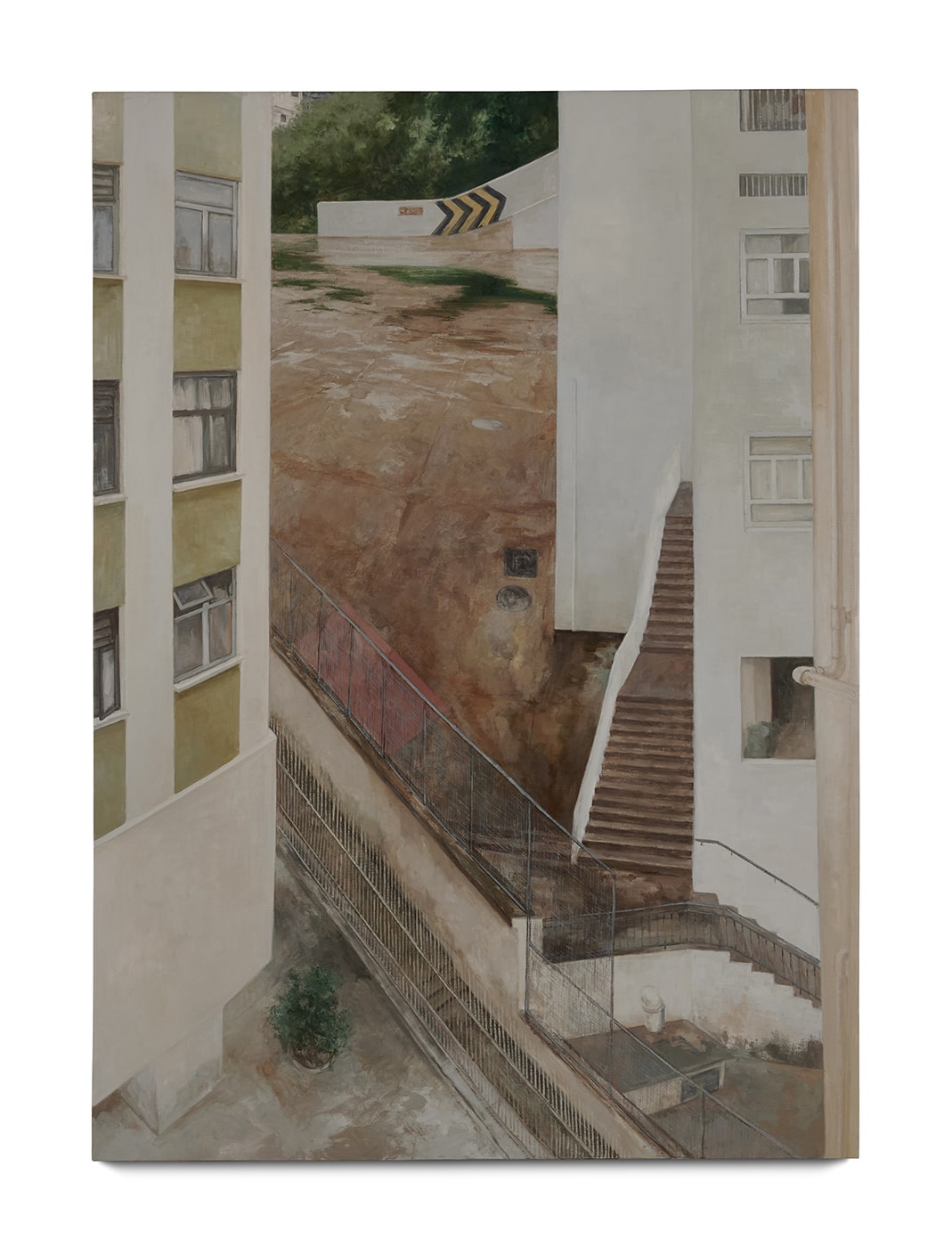

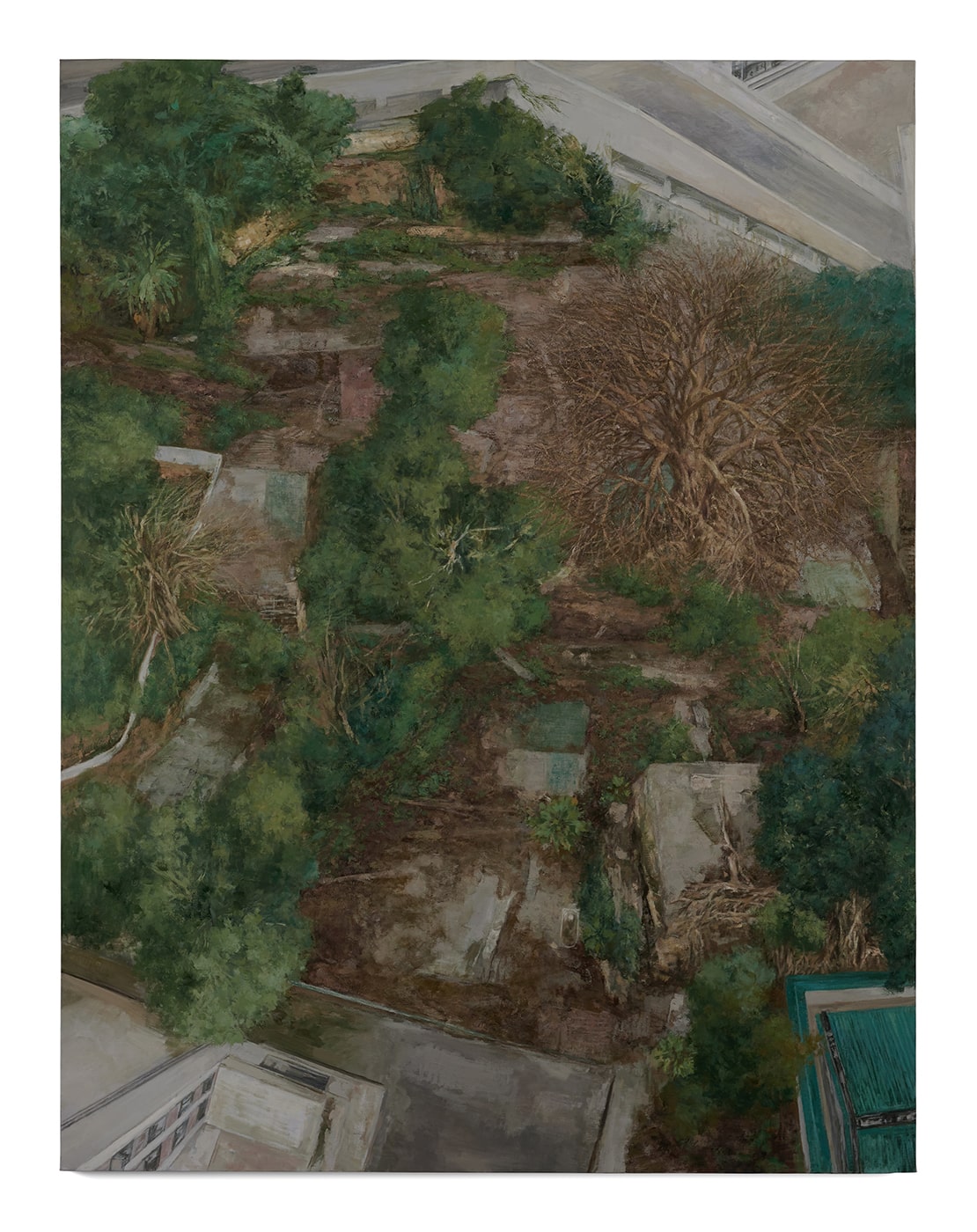

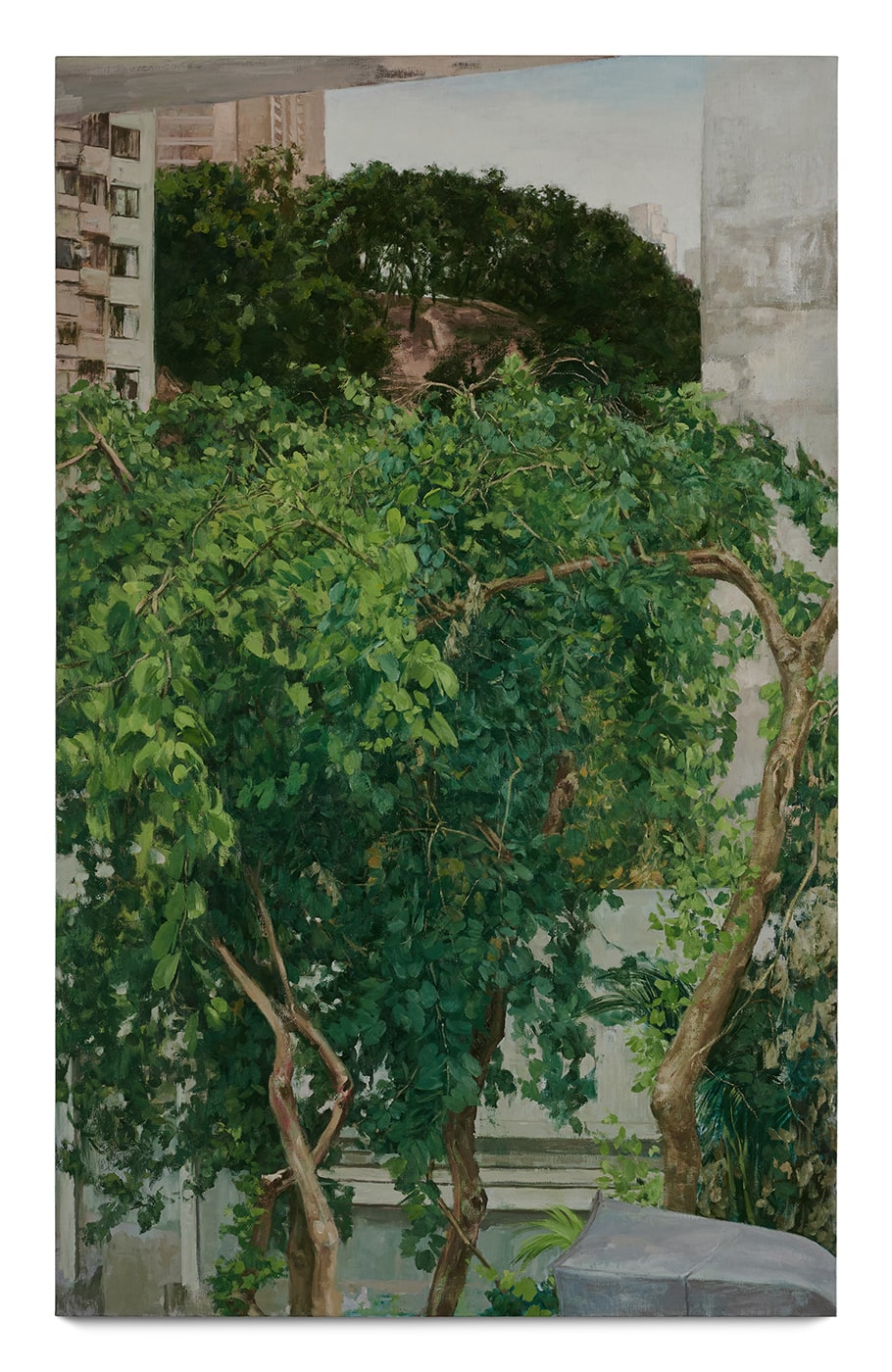

The artist’s affinity for the extraordinariness of ordinary life is exemplified by Sketchbook (2008-2020), a sprawling installation of 33 panels, where the artist painted scenes in the park when he peeps out of the window of his Kennedy Town studio. These paintings represent a keen observation for the environment, as greenery, cityscape and people form a mosaic of lived experiences. The artist notes that in his many years peering out of the window, he has witnessed the Bauhinia tree grow from a treeling to a flowering tower providing shade for park goers. The growing bauhinia trees, the aging inhabitants, and the rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood, are the humble and vastly generative soil of Yeung’s art creation.

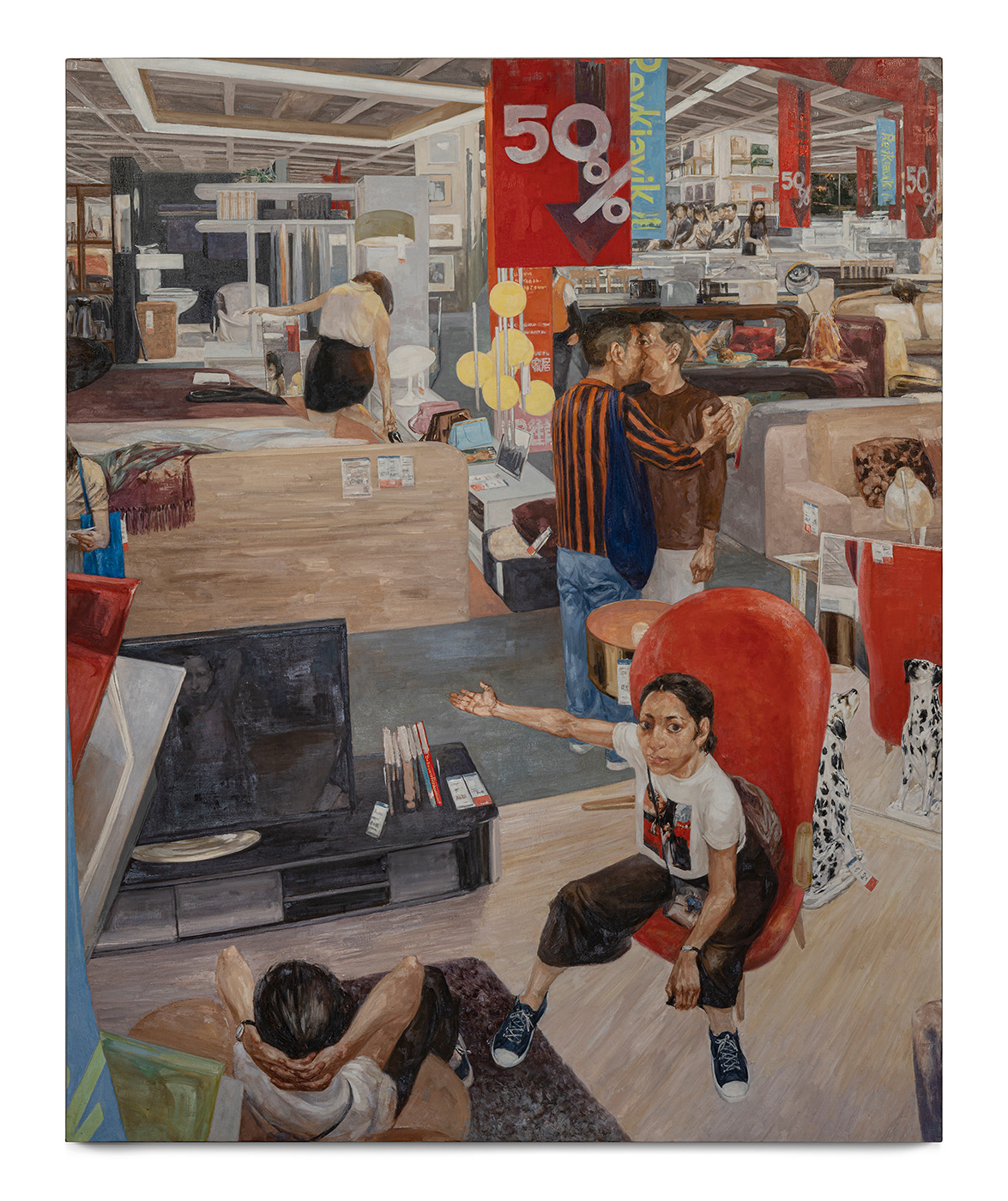

With flair and ingeniousness, Yeung tirelessly depicts the daily lives of the working class and the proletariat, giving them the larger-than-life attention and representation that they are often deprived. His paintings contain many entry points, opening multiple puncta that pierce through the fog of our mundane and desensitized existence. They hold up a poignant and personal mirror to our own lives, and reveal the blind spot of our perceivably fixed self. In Daily Practice, Yeung coaches us that the act of looking is the ultimate act of self-discovery, and the most gracious gift of compassion, optimism and hope.

)