Curated by Nick Yu

“Holy Mosses” is a group exhibition of eight female or gender non-binary artists. The exhibition asks a pivotal question: how do we give expression to a world where all genders thrive in freedom? Resisting essentialist narratives, and cultural and biological determinism, this ensemble of artworks explores the non-binary fluidity of gender, its expression across the amorphous expanse of organic nature, and its ensuing mythological imagination and daydreaming across cultures and peoples.

There are two ways to imagine a trans-gender world. One way is to arrive at a post-human planet queered by future technologies. Another way is to rewrite our ancient herstory, revisiting the pre-human world in its biological diversity and exuberant myths. Both routes are full of vivacious images, sensuous textures and roaming horizons stretching beyond our current knowledge.

Let’s start from one of the beginnings. Plants wear their reproductive organs prominently as flowers, who display their male and female sexual organs concomitantly. All genders coexist and transpose in the same being, neither scorning nor dominating the other. Their femininity and masculinity coproduce and collaborate seamlessly, ever since time immemorial.

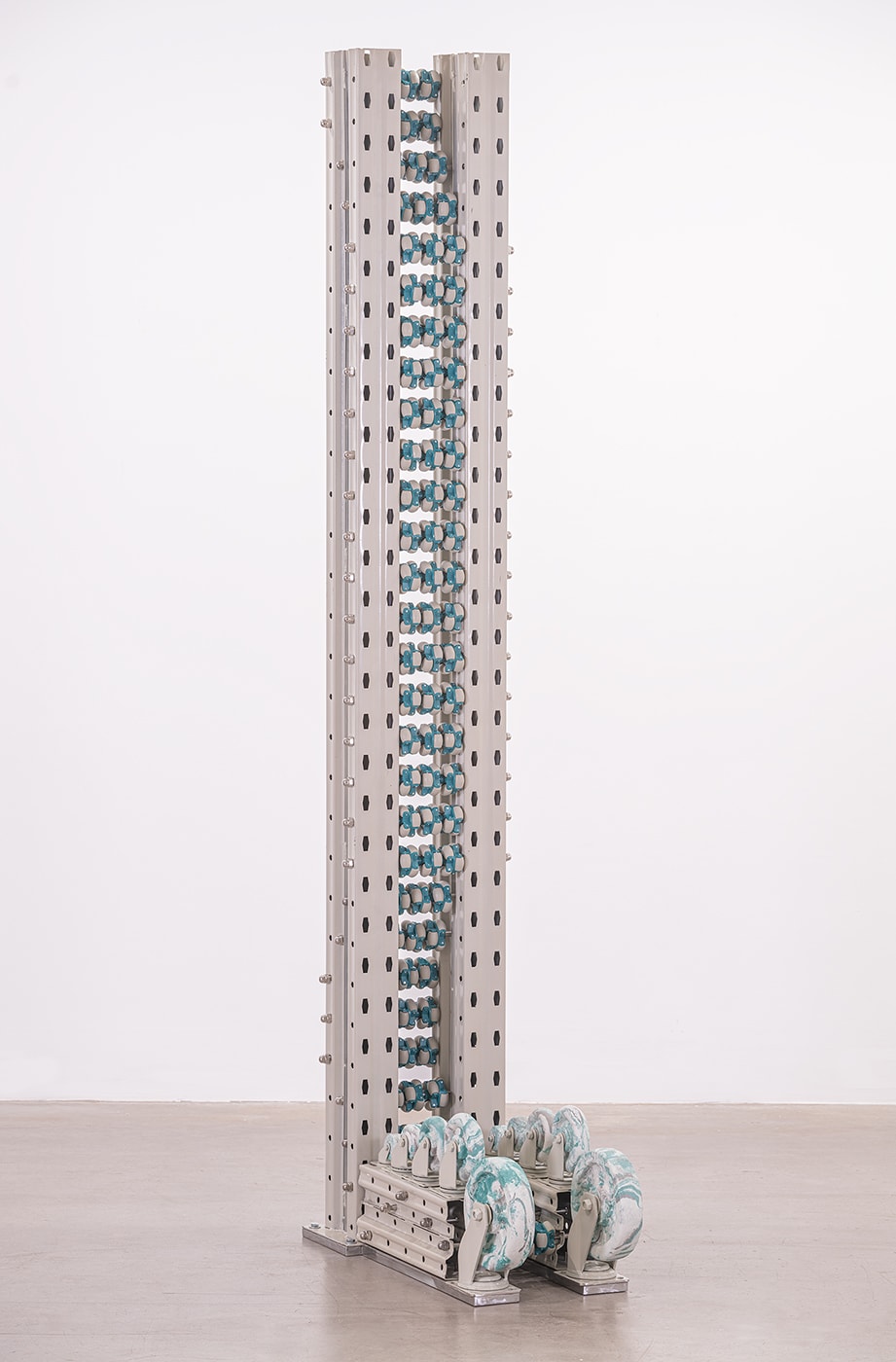

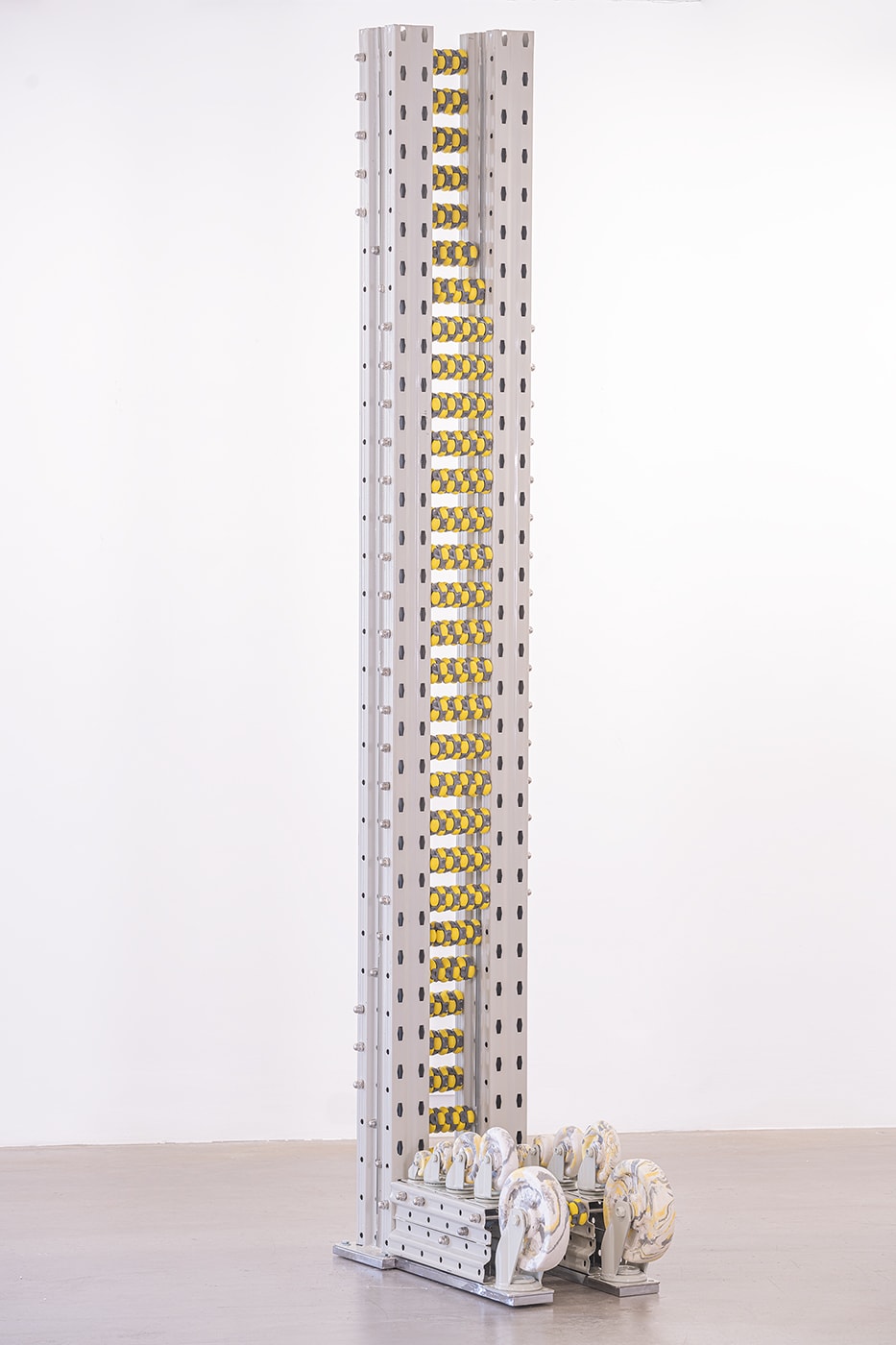

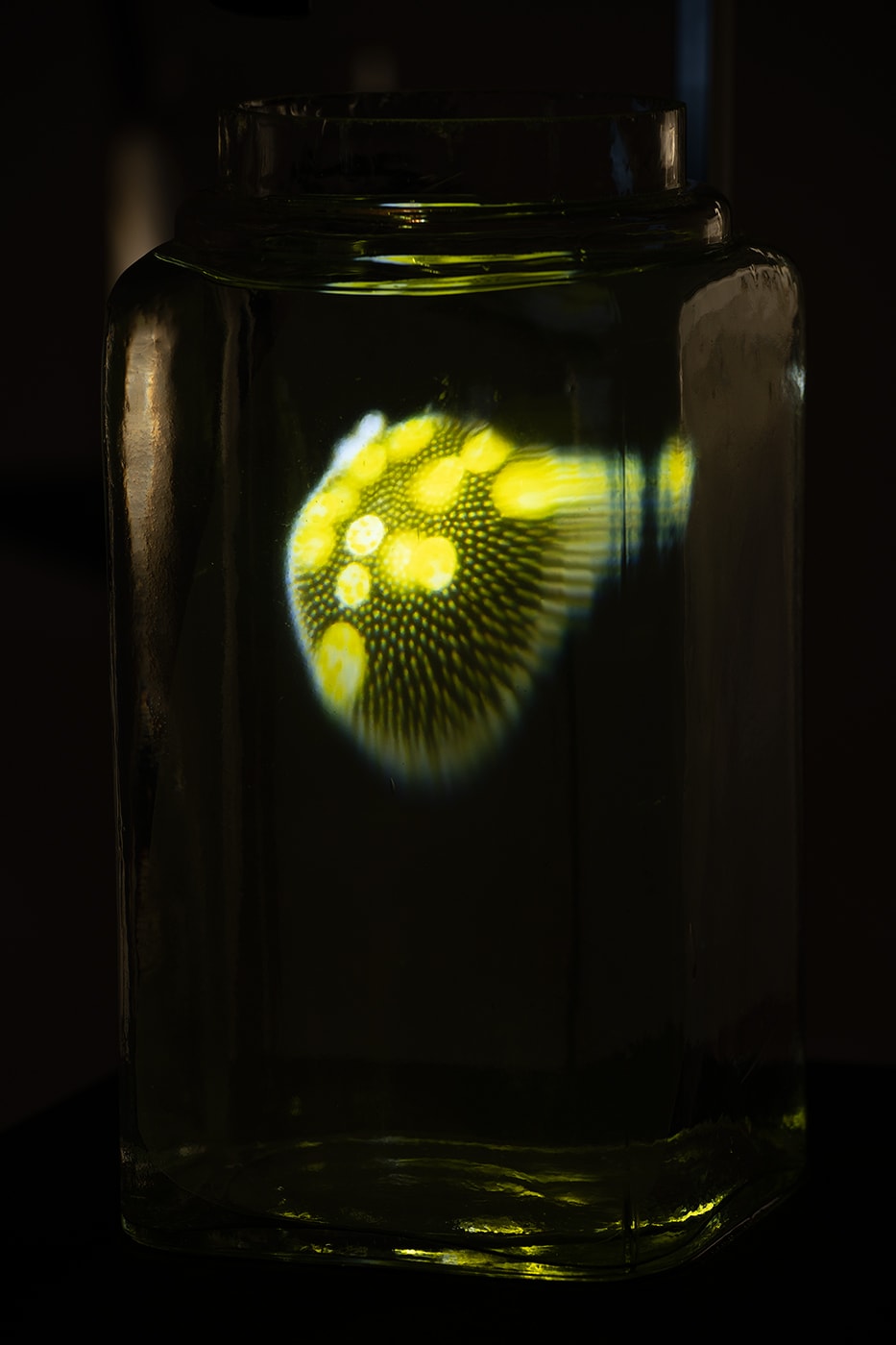

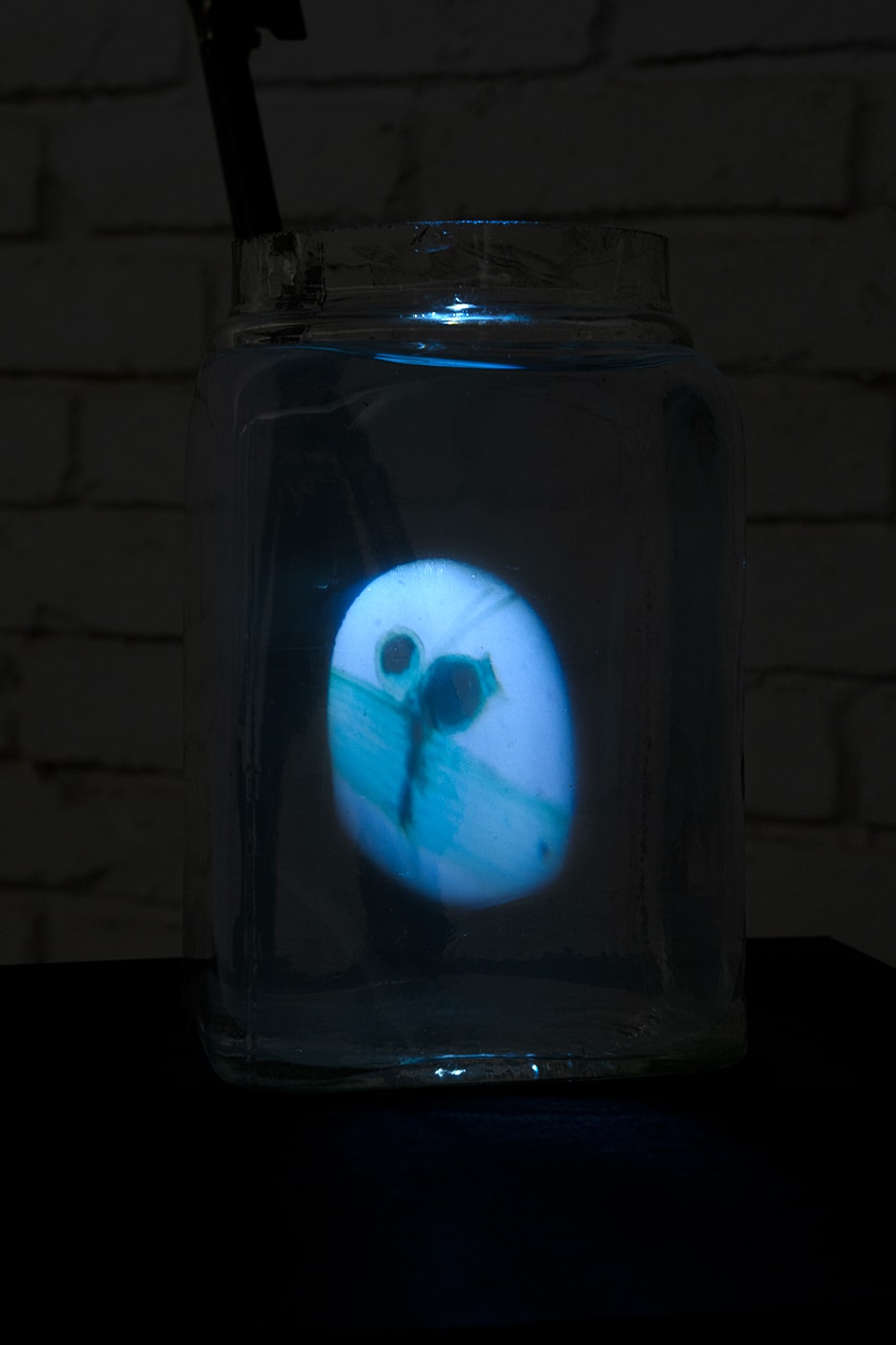

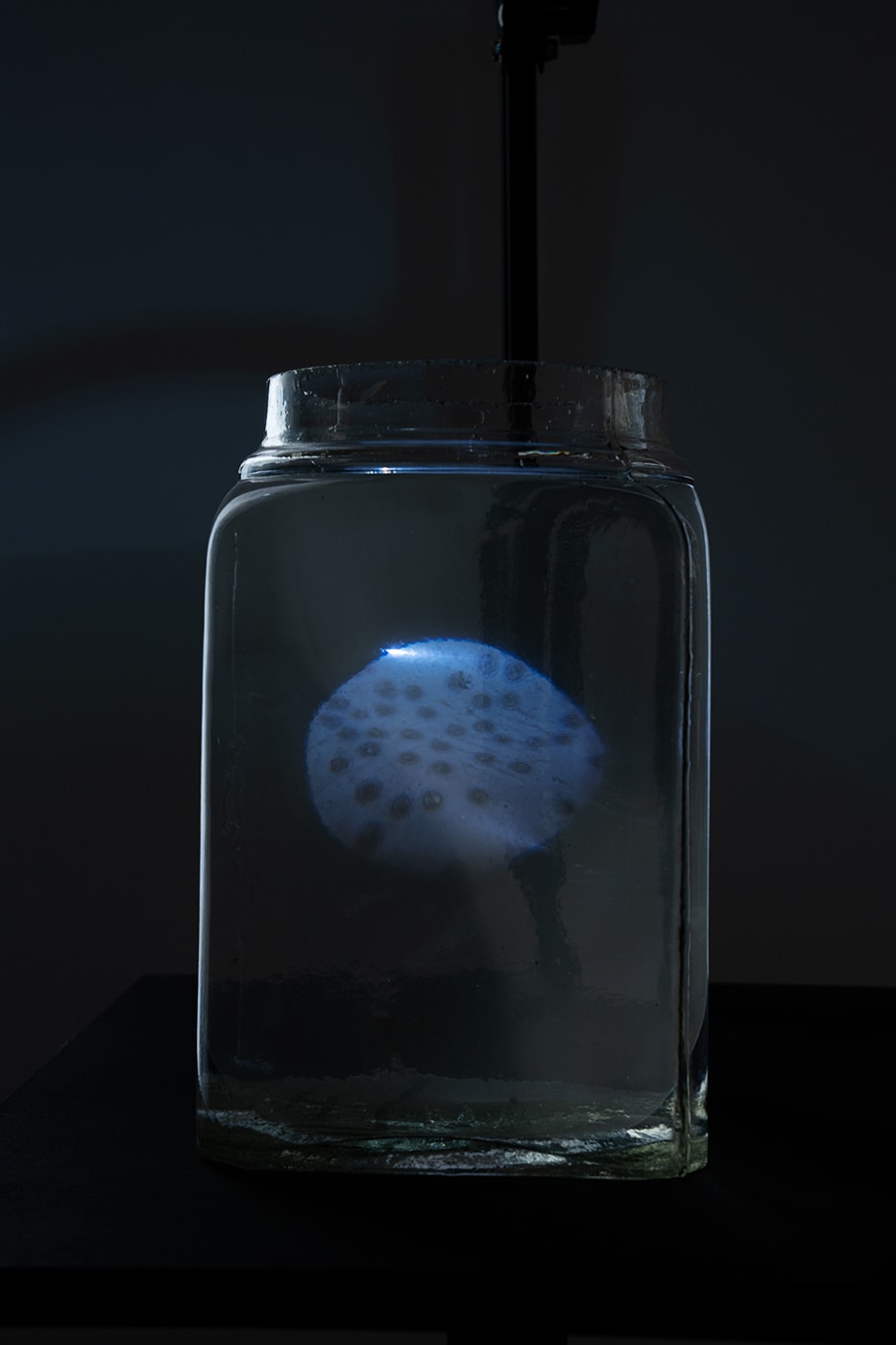

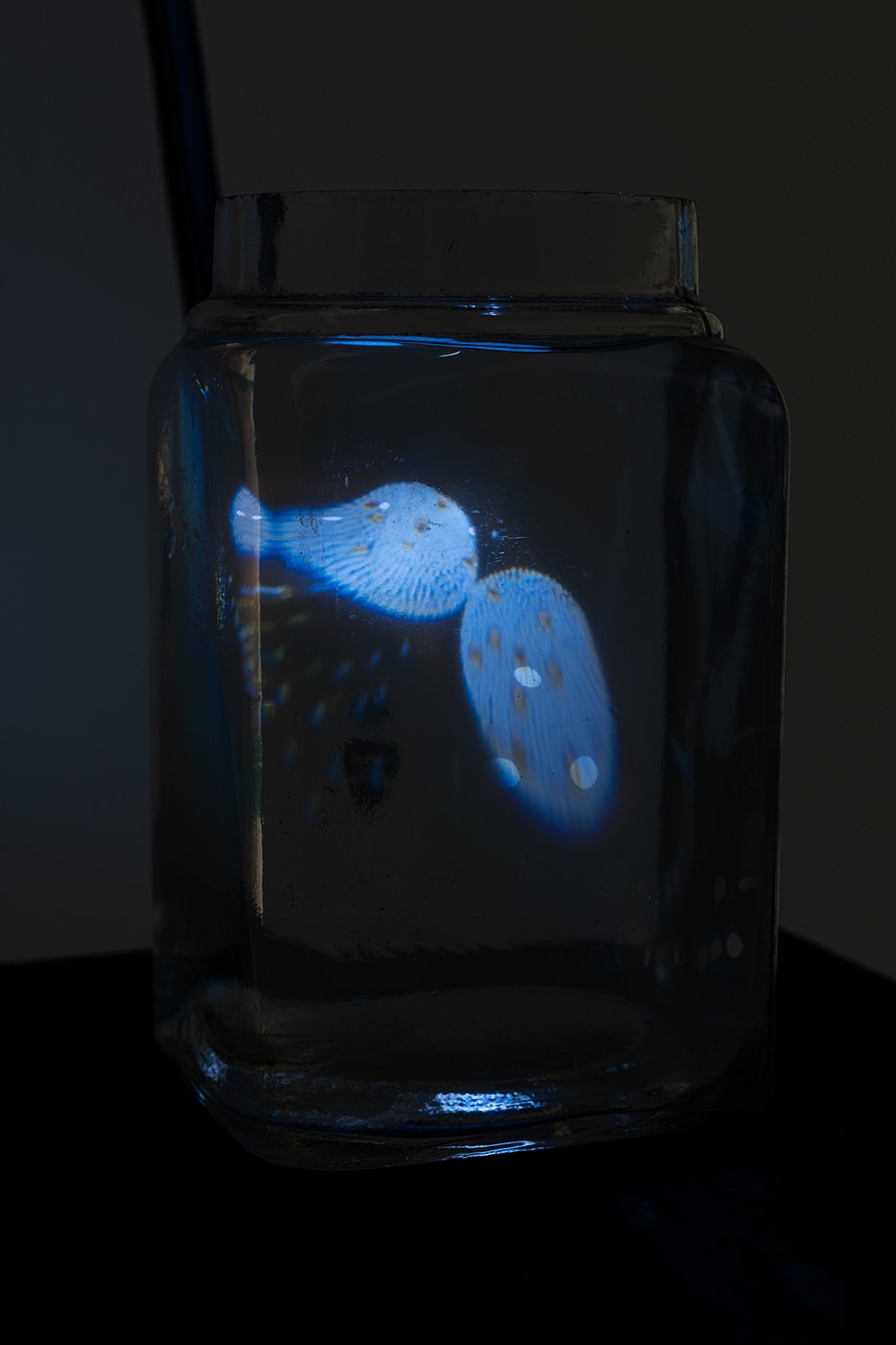

Tracing the first plants, So Wing Po creates an installation that articulates the cellular view of underwater algae, visualizing the ancient genetics that influences observable sexual characteristics. Leelee Chan erects towering sculptures made with industrial materials, resembling giant caterpillars capable of colorful evolution, transformation and metamorphosis. Zhang Ruyi makes cement sculptures of various succulents and cacti, whose seductive flowers are often the only green growing in the arid desert. Although showing just a fraction in the diversity of the botanical and zoological world, they present a rainbow of gender differences and adaptability to the environment.

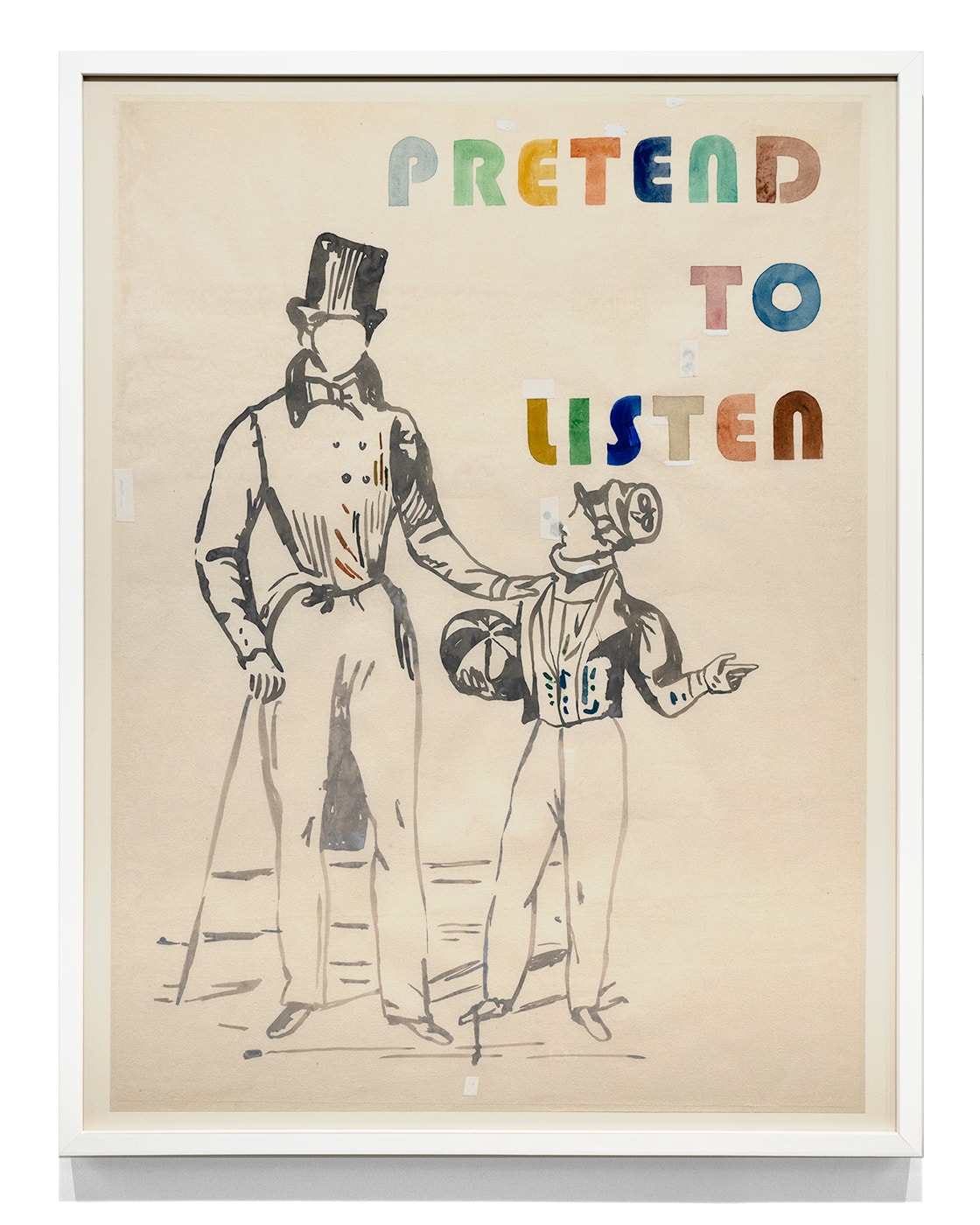

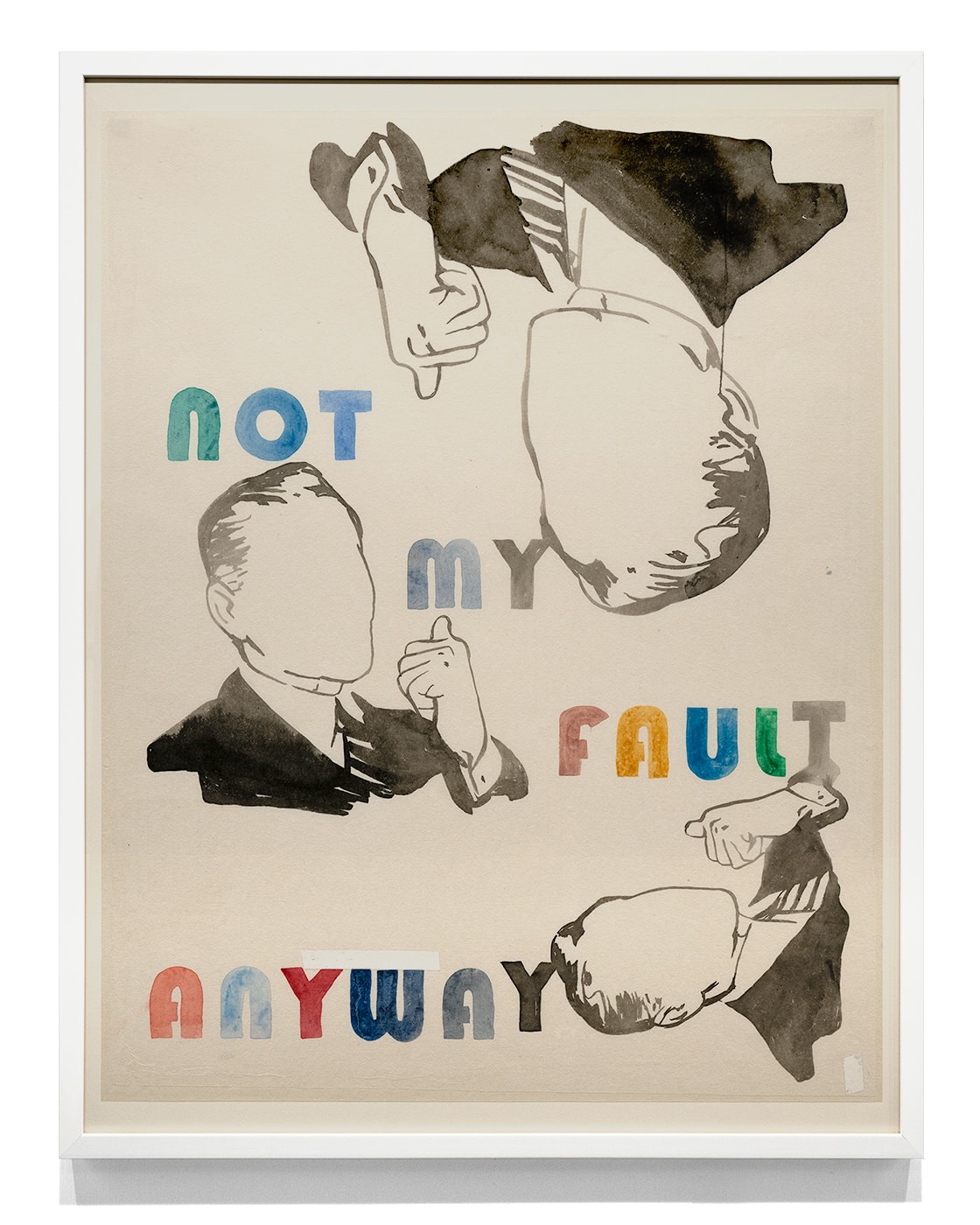

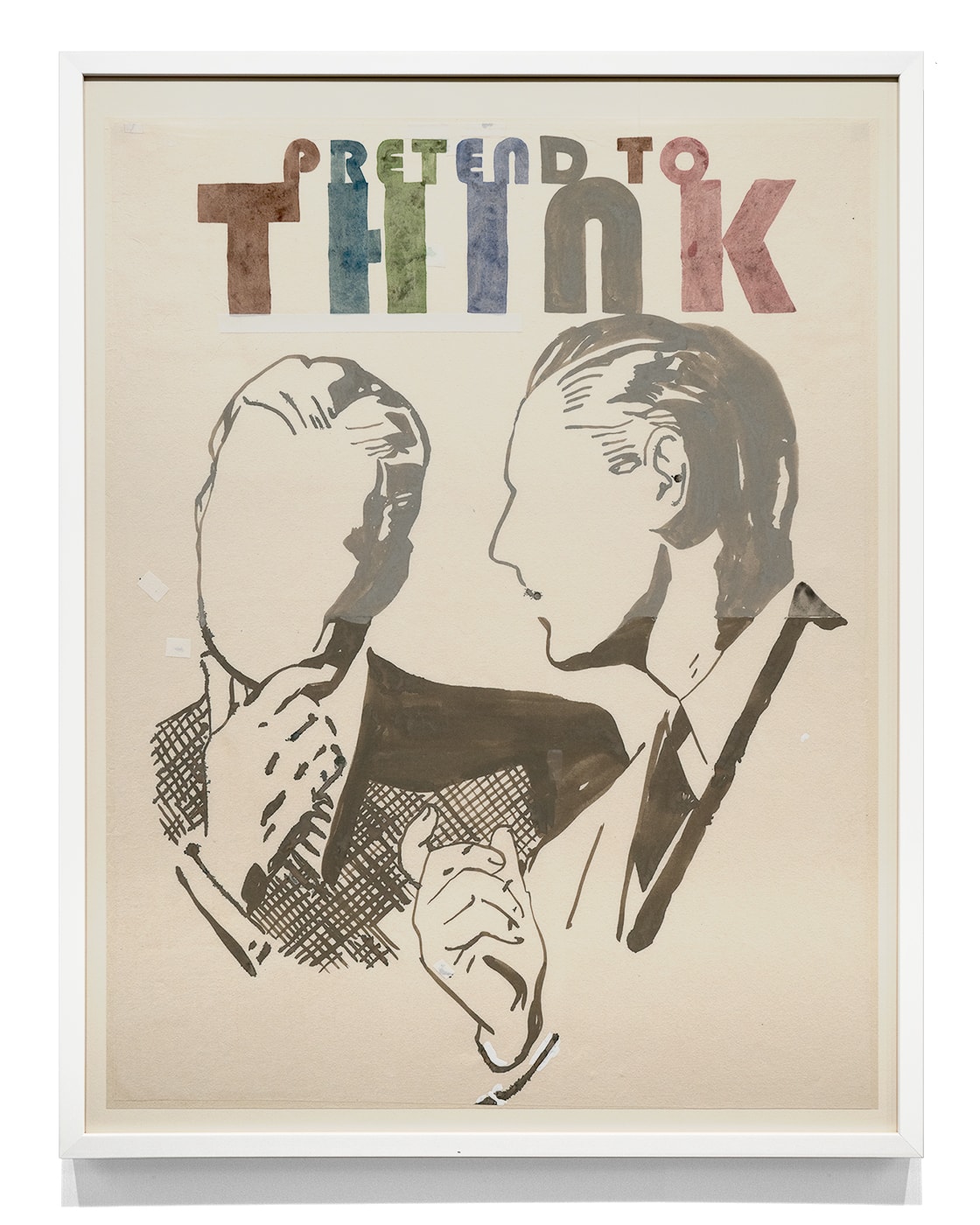

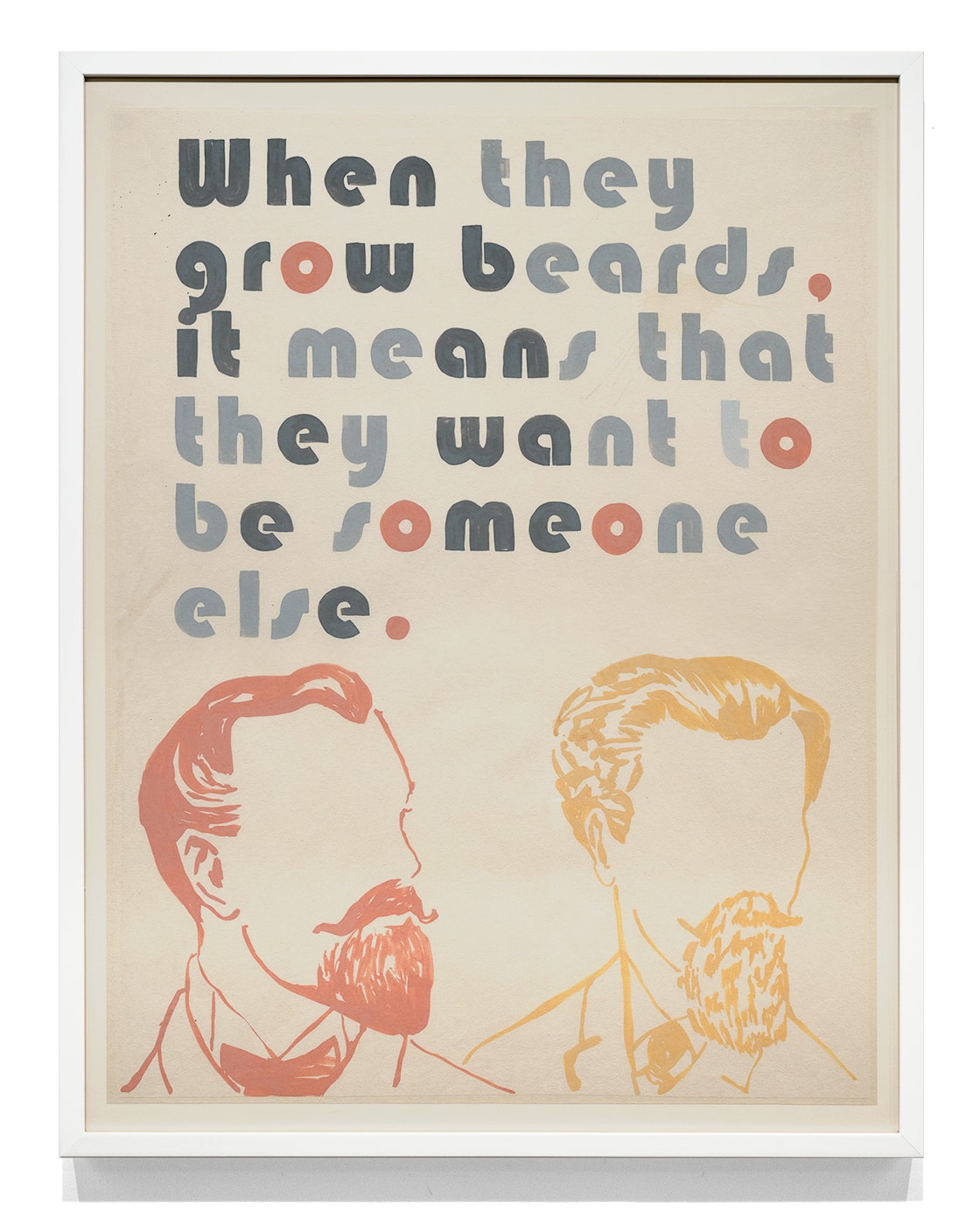

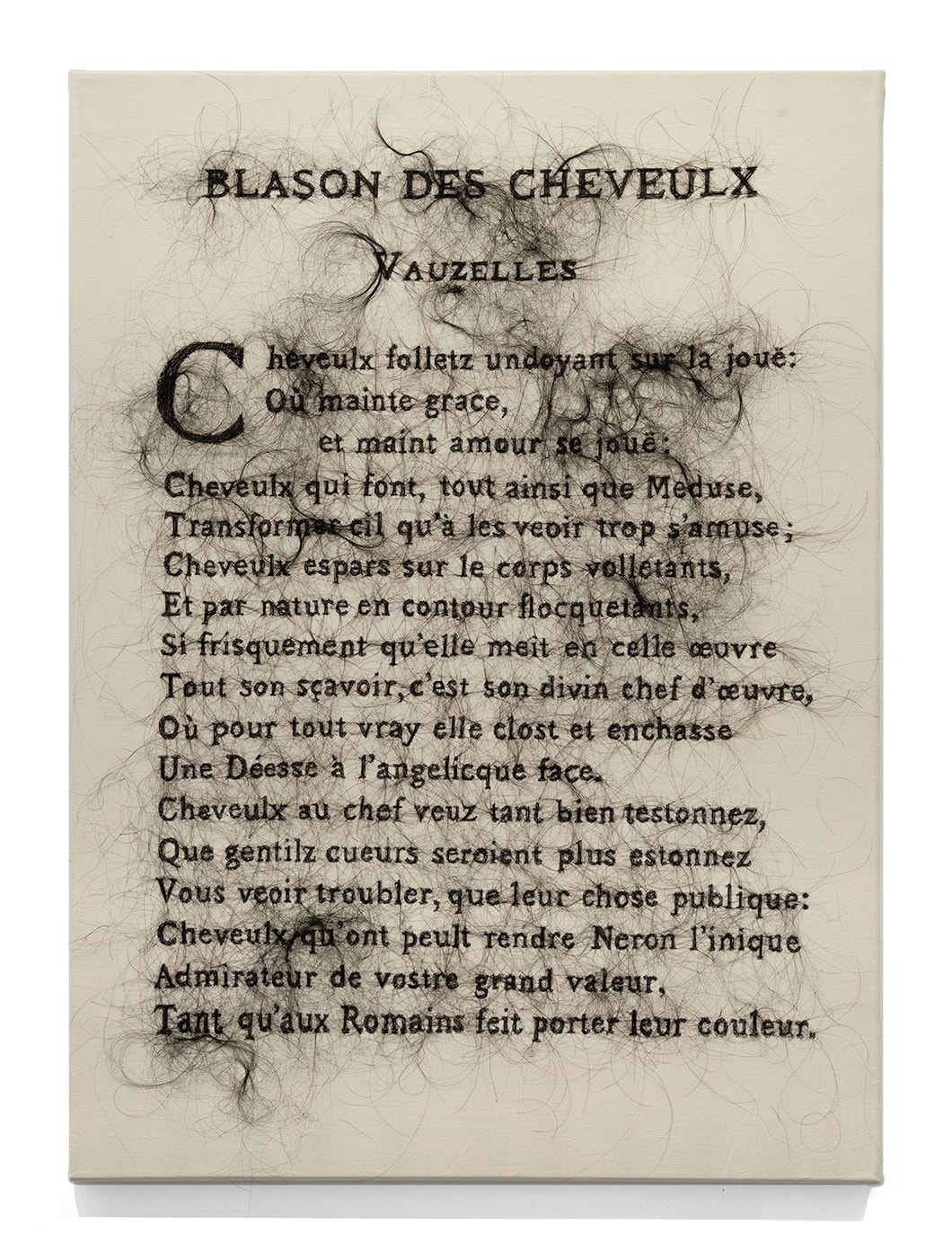

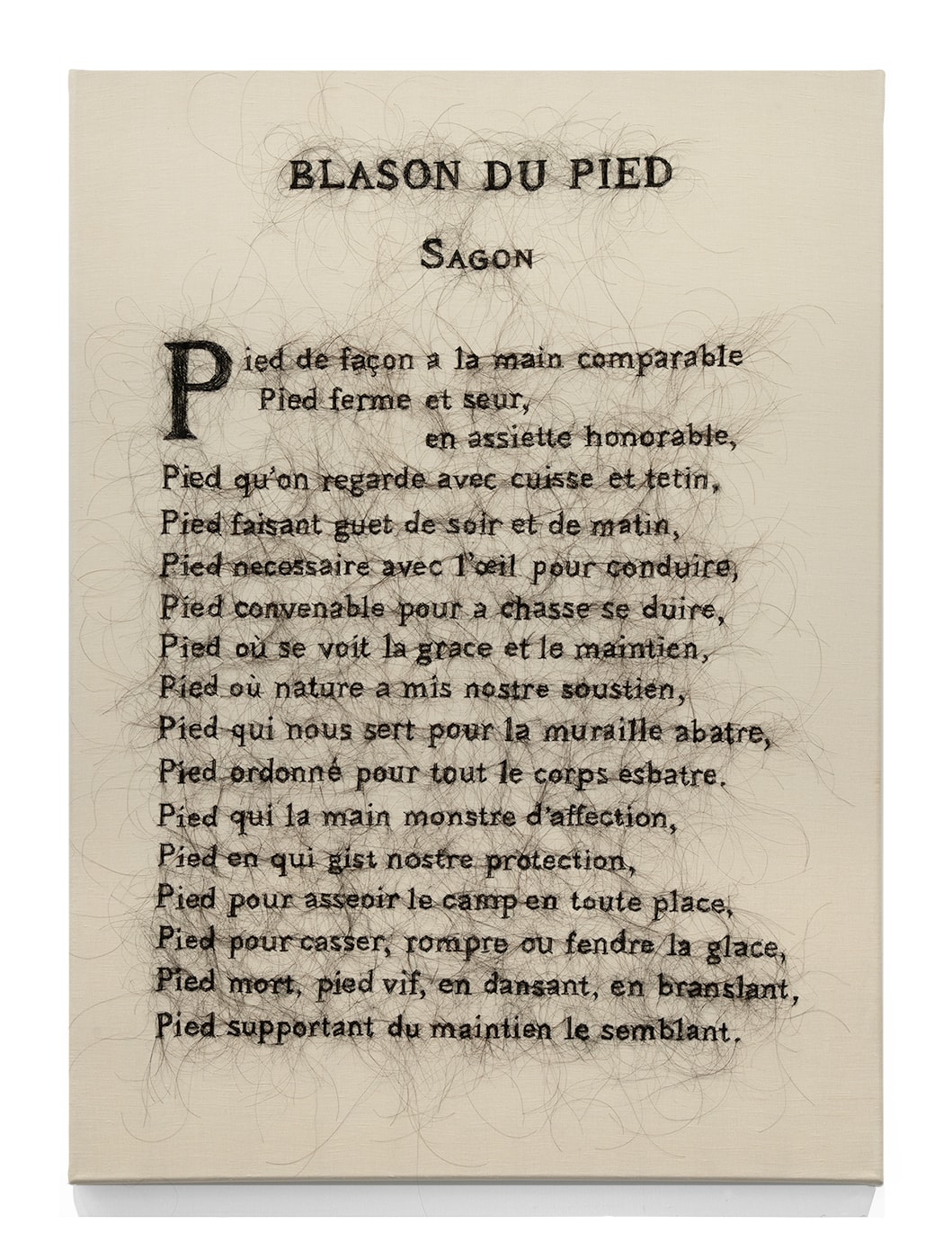

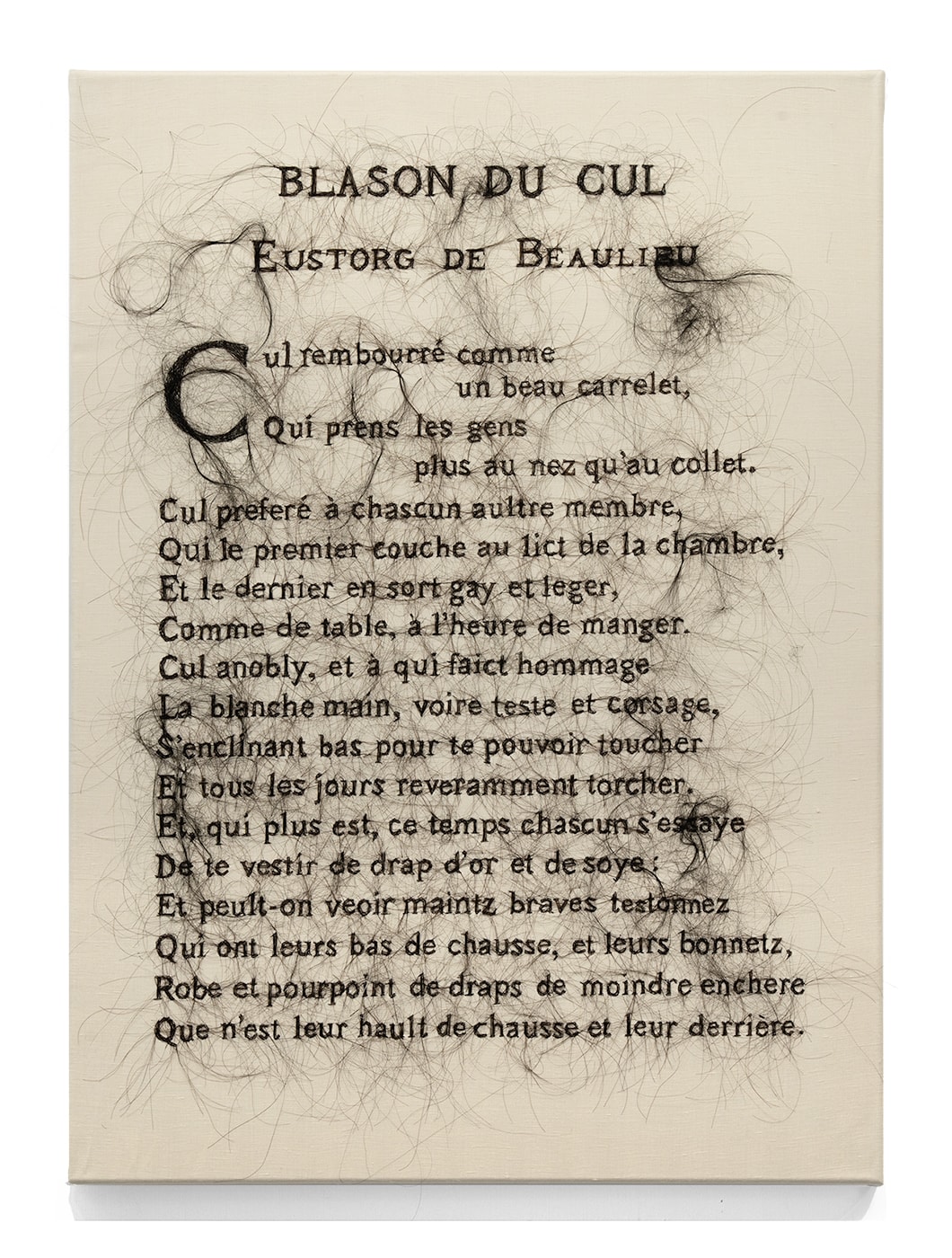

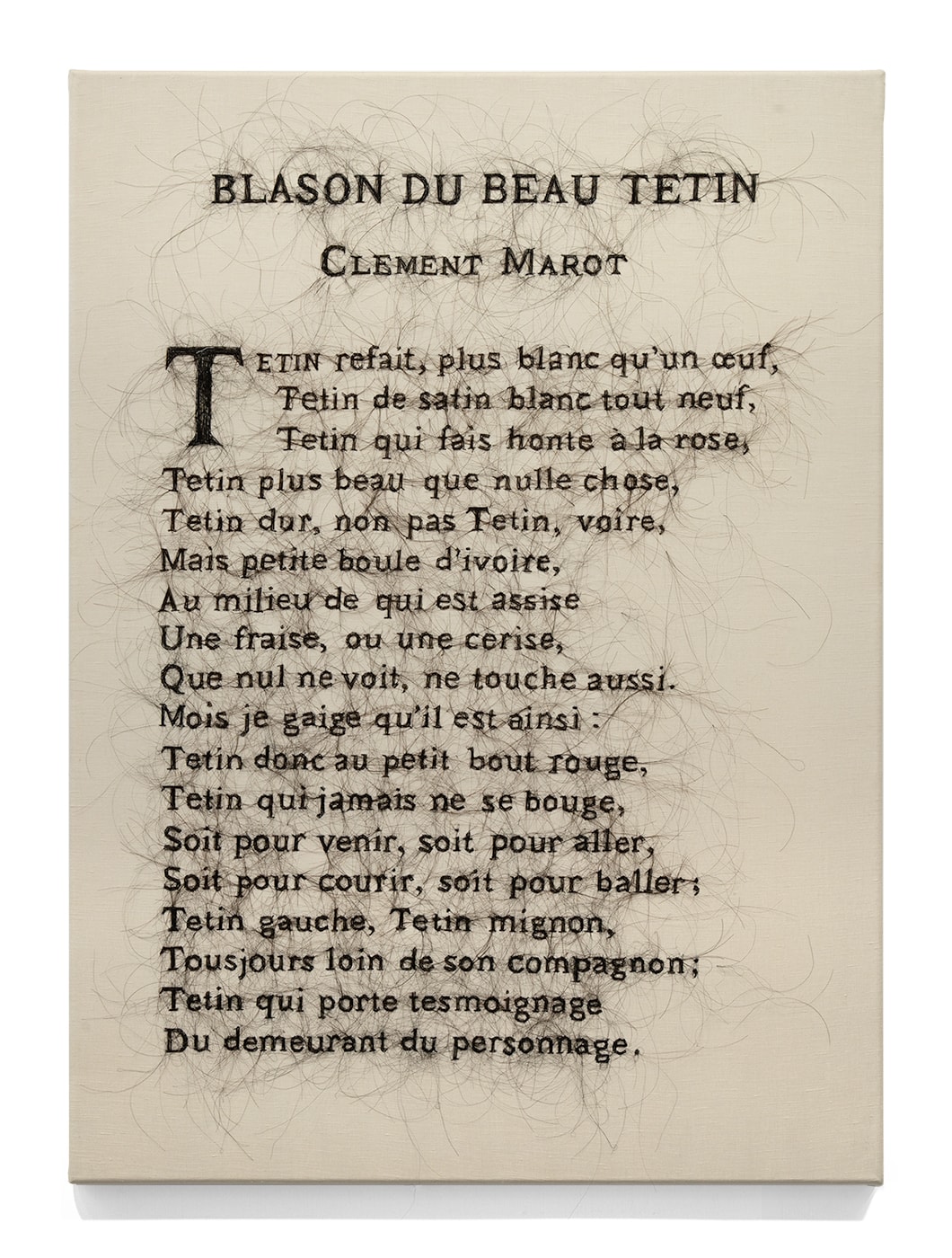

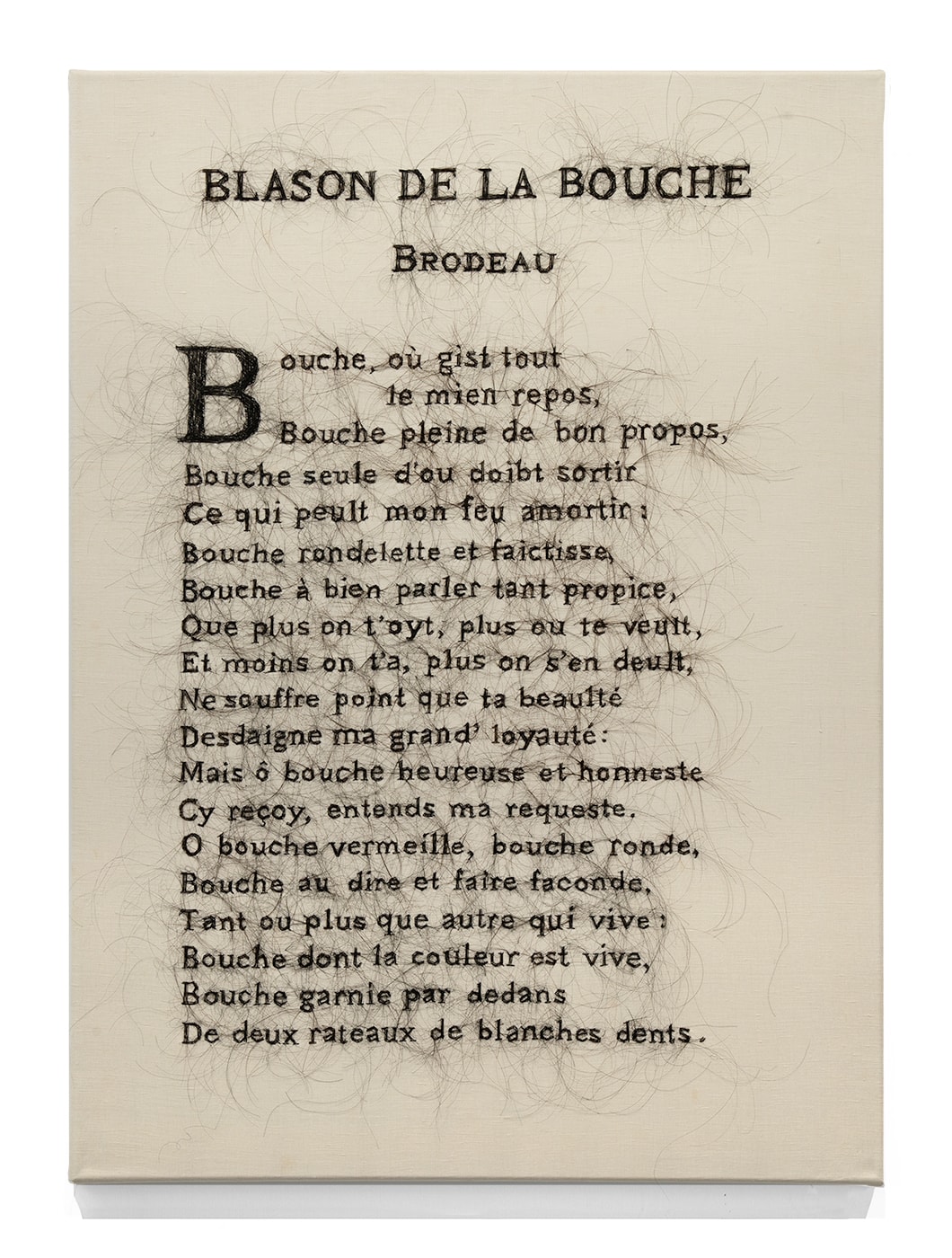

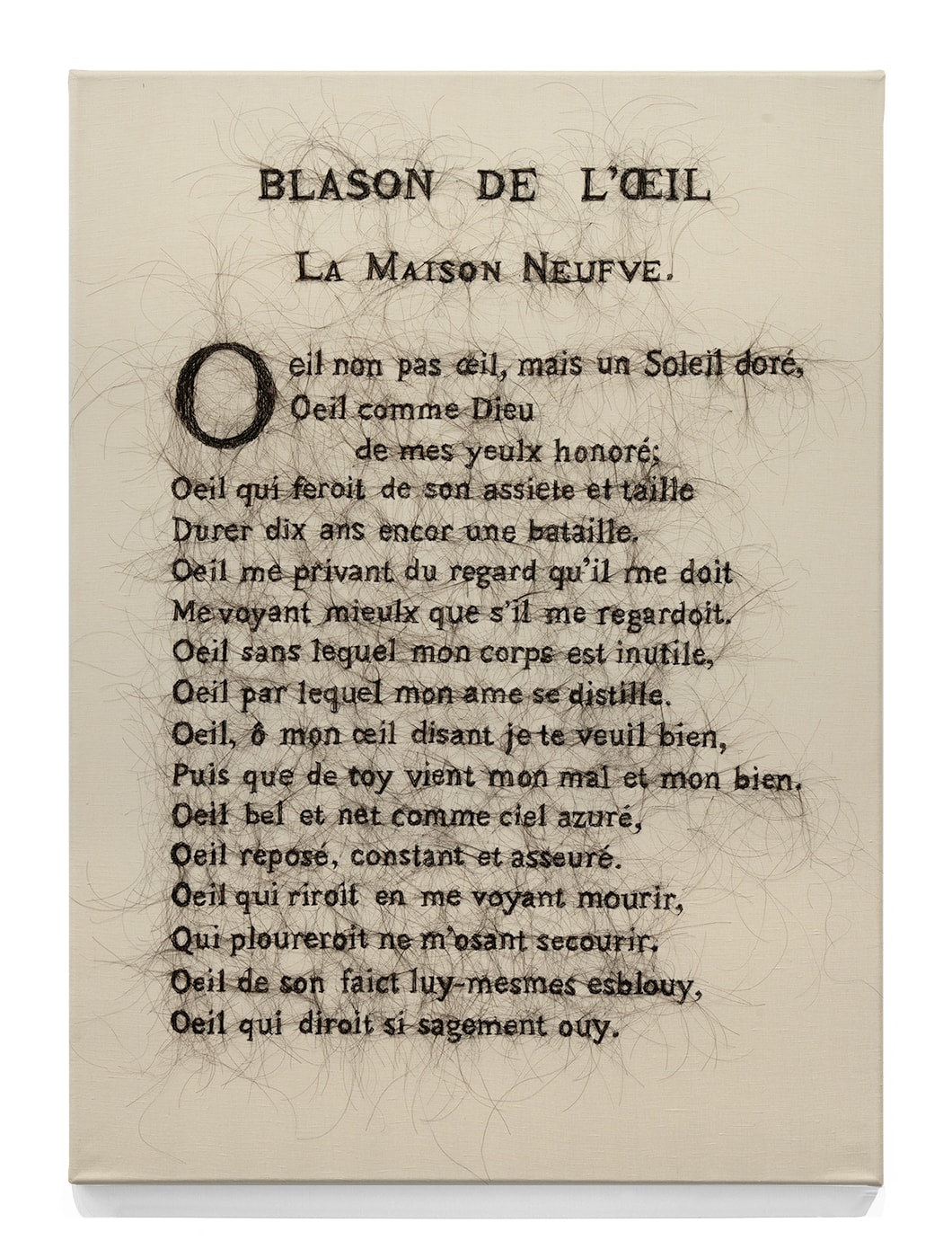

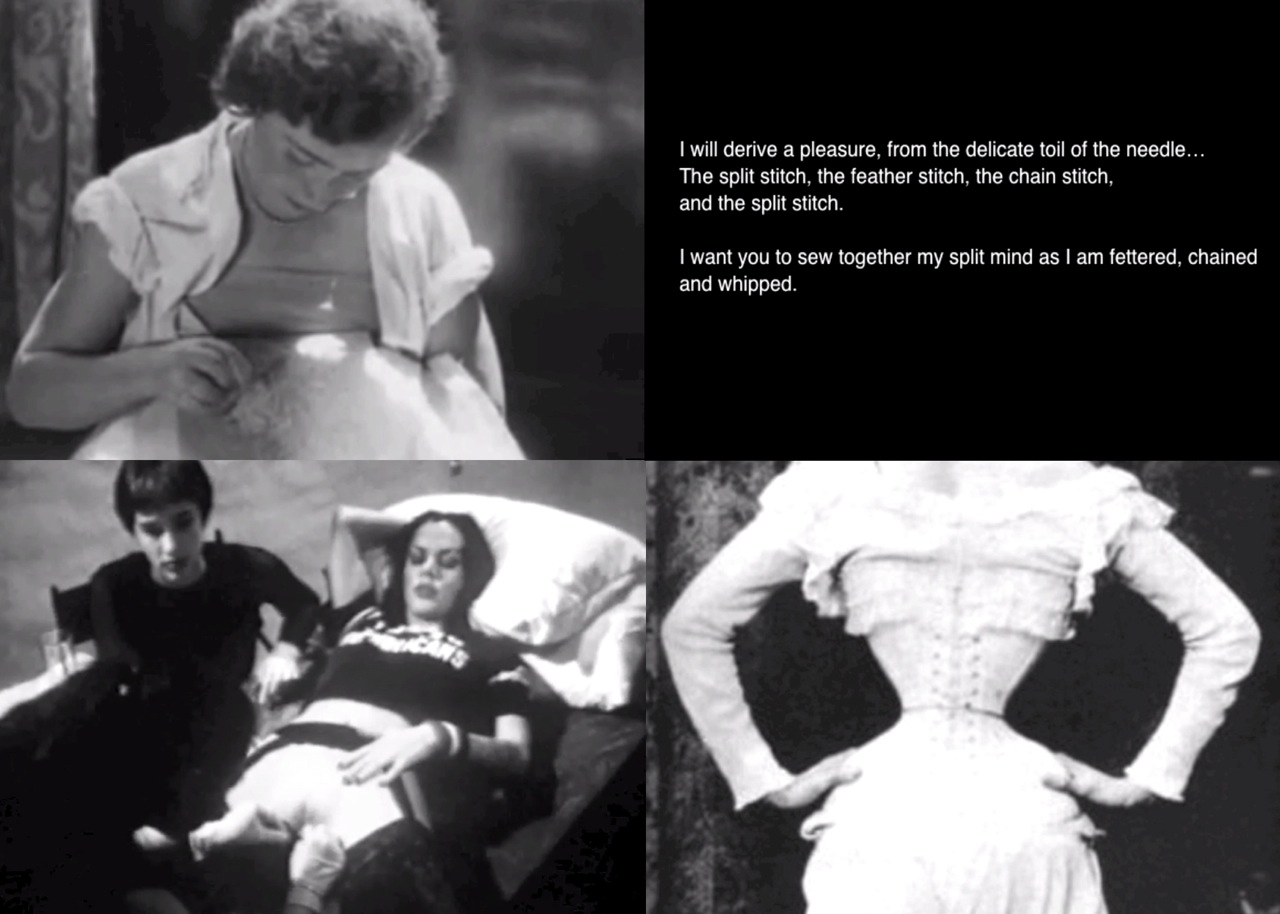

The fruits of their labour have magical qualities, containing erotic hormones and aphrodisiac juices, transmitting intersexual prowess to their consumers. Using hair embroidery, Angela Su narrates a series of medieval French poetry that individually praises and fetishizes females’ body organs. Pixy Liao poses with her boyfriend in a series of photographic self-portraits, staging an intimate relationship where gender roles are playful, fungible and negotiable. Wong Wai Yin satirizes gender stereotypes in He She It and the nativity scene, and rethinks the age-old fallacies imbued in the gendered pronouns of the Anglophonic Christendom.

Beneath the History and Science of men is the multiplicity of mythologies, alive with androgynous demigods and cross-gender reveries. In a lyrically confessional video essay, WangShui relays the edicts of feng shui and creatures in The Classic of Mountains and Seas, as their drone camera flies through the orifices in Hong Kong’s residential buildings. Victoria Sin performs in drag as they embody hyper-feminized characters, questioning processes of looking and desiring, identifying and objectifying, speculating and marginalizing.

)